1

people have died from curable diseases

since this page started loading...

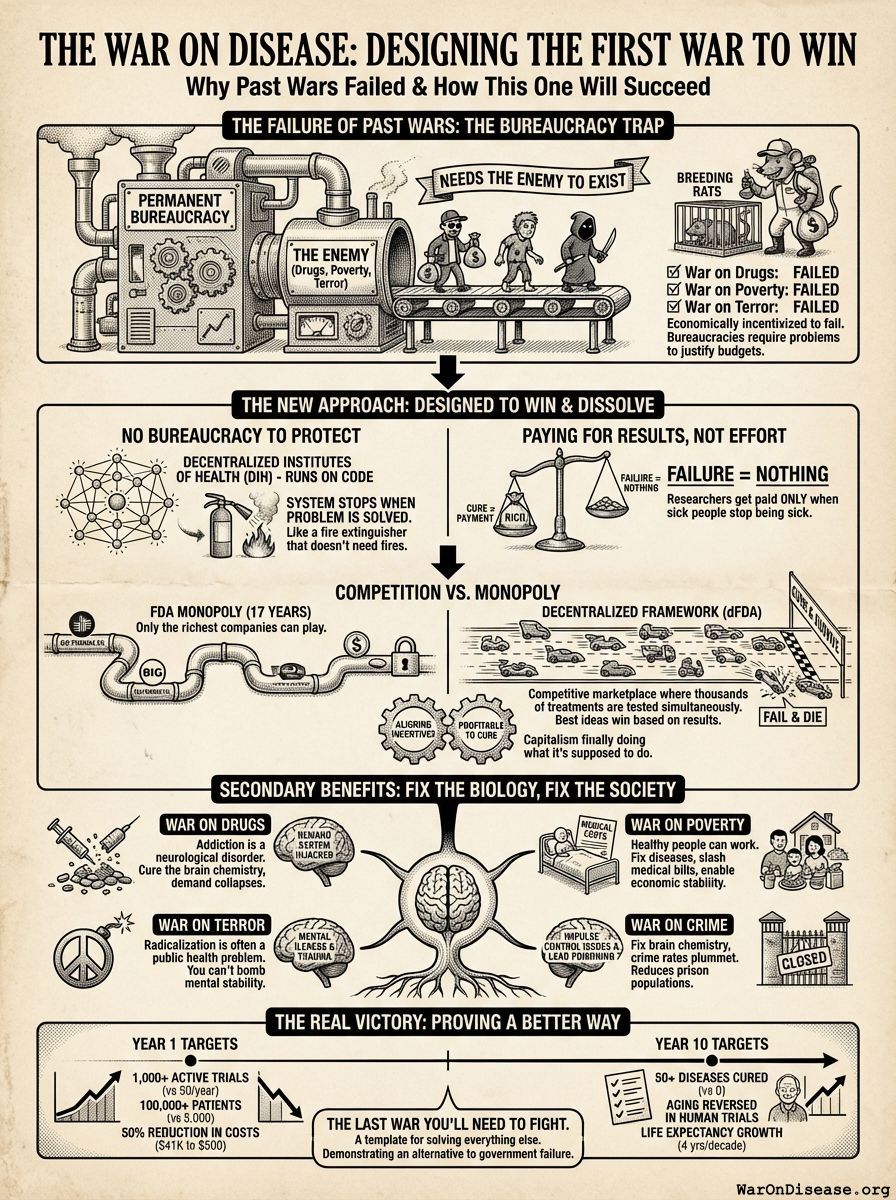

Every government “War on X” (Drugs, Poverty, Terror, Christmas) has been a spectacular failure.

This is not a coincidence. It’s economics.

When you build a permanent bureaucracy to fight something, that bureaucracy needs the enemy to exist. Otherwise, everyone loses their jobs.

The DEA needs drug dealers. The War on Terror needs terrorists. The War on Poverty needs poor people. It’s like hiring an exterminator who breeds rats on the side. Technically profitable, definitely unethical.

On How to Design a War That Actually Ends

The War on Disease is different in one critical way: it’s designed to win and then dissolve into nothingness, like a therapy session that actually works.

Here’s what makes it different from every other doomed war on abstract nouns:

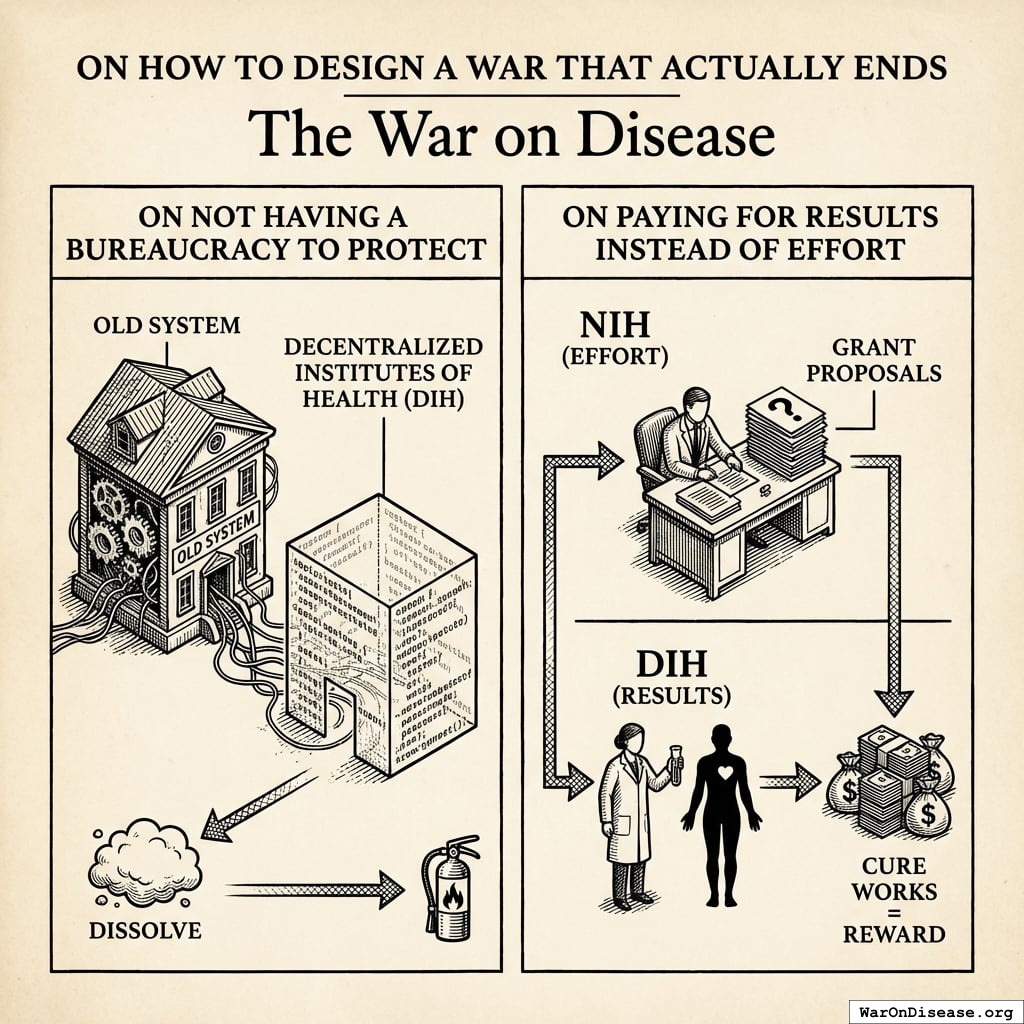

On Not Having a Bureaucracy to Protect:

Your decentralized institutes of health (DIH) runs on code, not committees. There are no headquarters. No permanent staff. No pensions to protect. No one whose mortgage depends on disease continuing to exist.

If we cure all diseases, the system just… stops. Like a fire extinguisher that doesn’t need fires to justify its budget. Straightforward concept, oddly novel in government.

On Paying for Results Instead of Effort:

The NIH pays scientists to write grant proposals about maybe someday potentially thinking about doing research.

Your decentralized institutes of health pays them when sick people stop being sick.

If a researcher’s cure works, they get rich. If it fails, they get nothing. This is how every other functional industry works, except government and academia, which explains a lot.

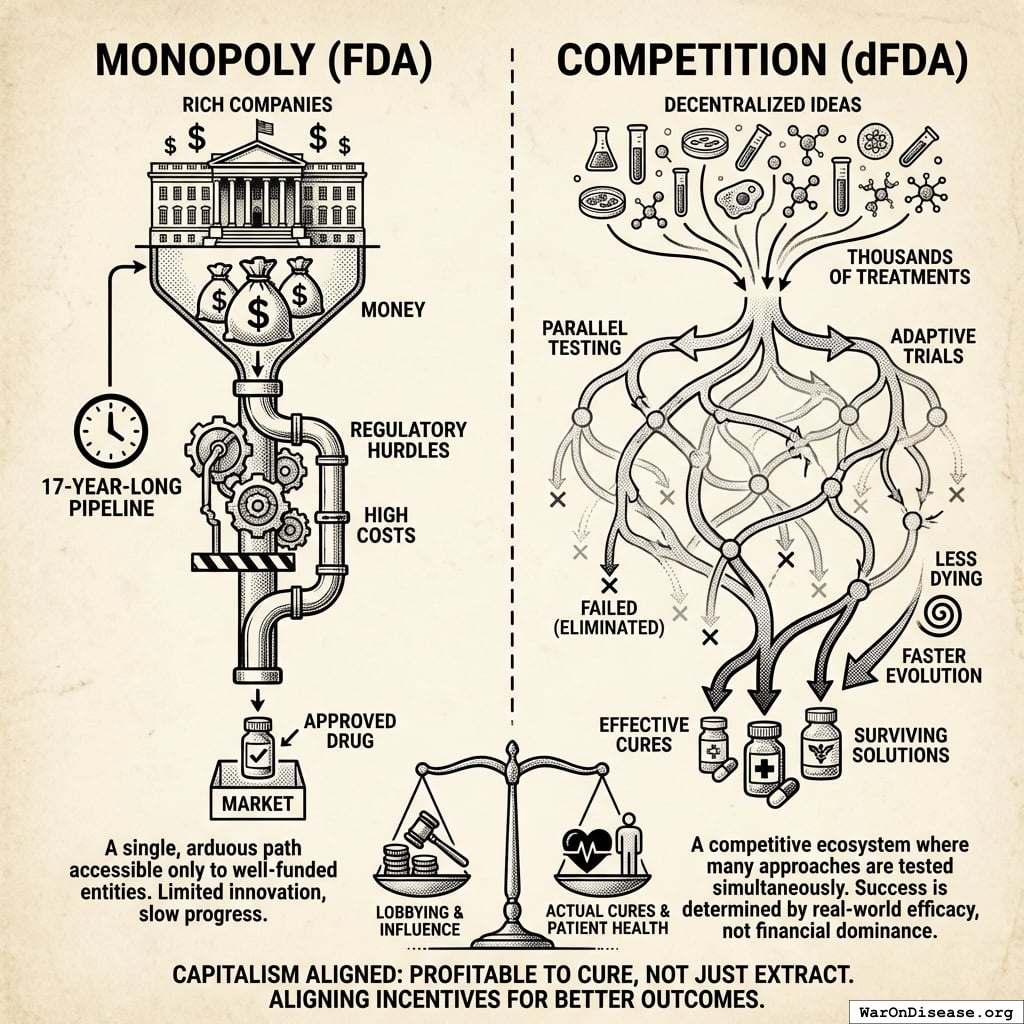

On Competition Versus Monopoly

The FDA creates a single, 17-year-long pipeline to approval where only the richest companies can play.

Your decentralized framework for drug assessment (dFDA) creates a competitive ecosystem where thousands of treatments are tested simultaneously and the ones that work survive. Like evolution, except faster and with less dying.

The best ideas win based on whether they actually cure people, not based on which company bought the most congressmen.

This isn’t a struggle of attrition. It’s a matter of aligning incentives. You’re not trying to make people better through moral persuasion or inspirational posters. You’re just making it more profitable to cure people than to let them die while extracting their savings.

It’s capitalism actually doing what it was supposed to do, which is pleasant if somewhat overdue.

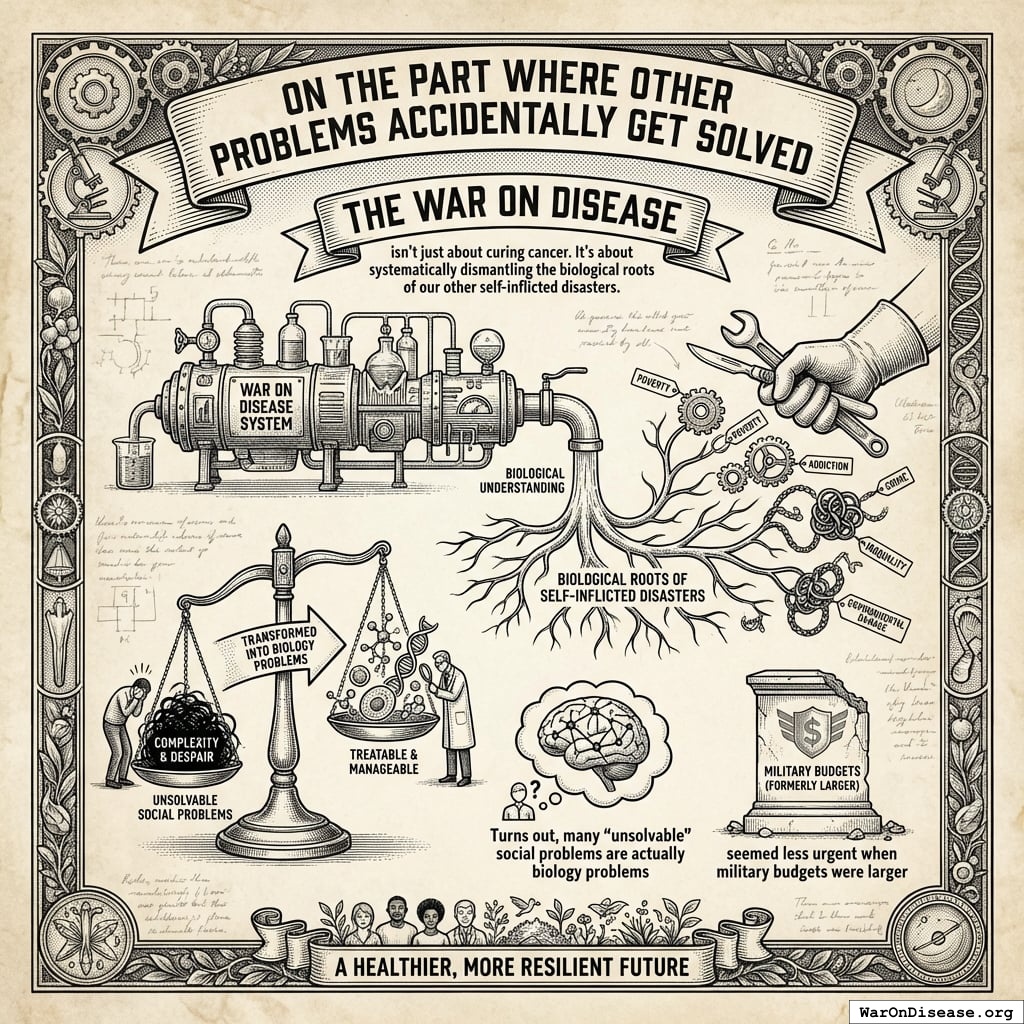

On The Part Where Other Problems Accidentally Get Solved

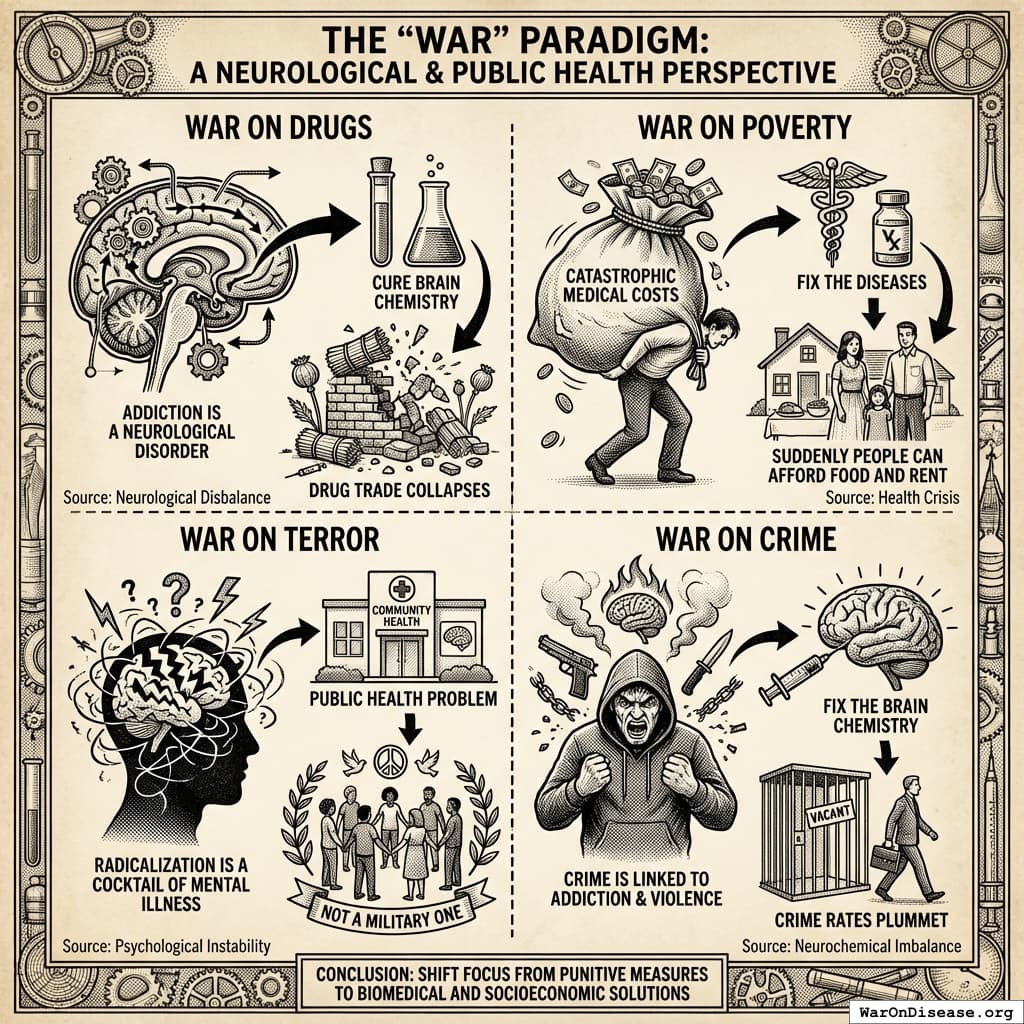

The War on Disease isn’t just about curing cancer. It’s about systematically dismantling the biological roots of our other self-inflicted disasters.

Turns out, many “unsolvable” social problems are actually biology problems that seemed less urgent when military budgets were larger.

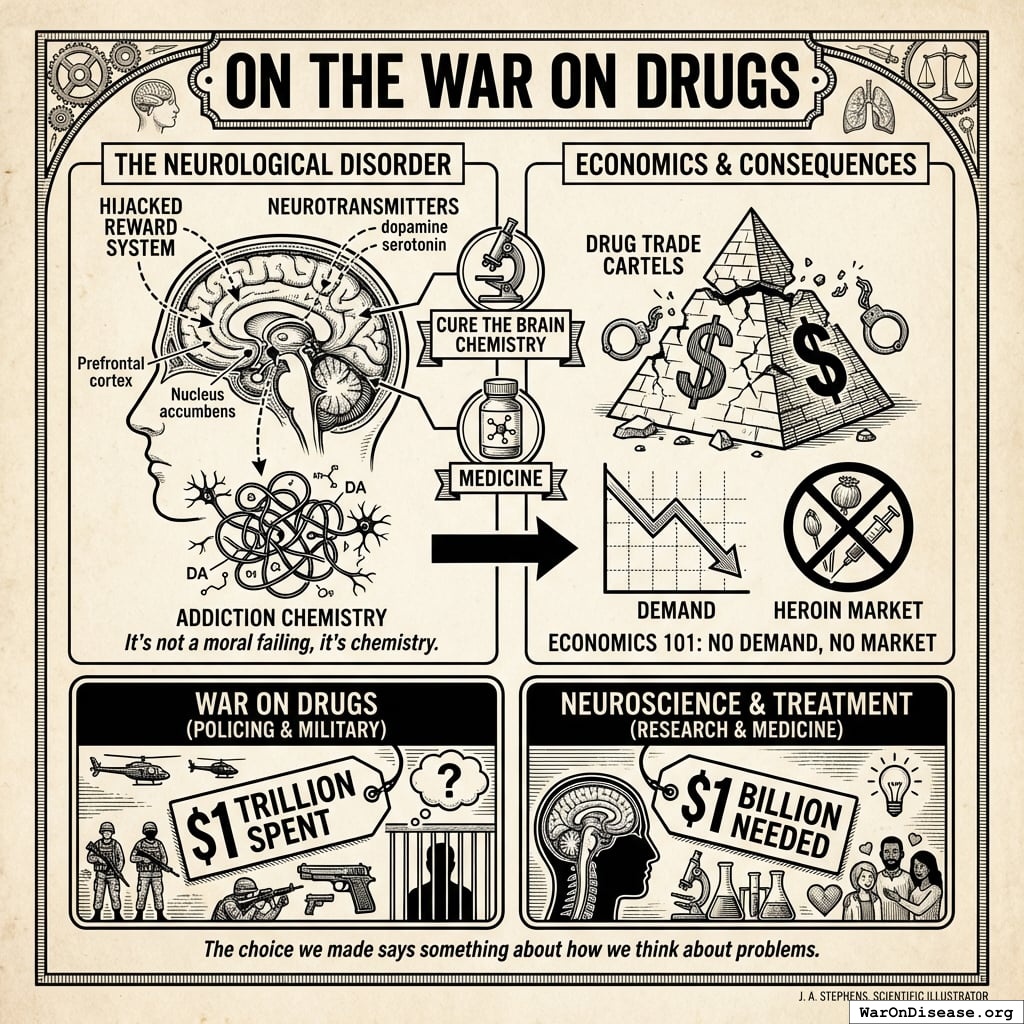

On the War on Drugs

Addiction is a neurological disorder. Your brain’s reward system got hijacked. It’s not a moral failing, it’s chemistry.

Cure the brain chemistry, and the drug trade collapses. Cartels can’t sell heroin if nobody’s brain wants heroin. Economics 101: no demand, no market.

We spent $1 trillion fighting drug dealers with guns. We could have spent $1 billion fixing the neurochemistry with medicine. The choice we made says something about how we think about problems.

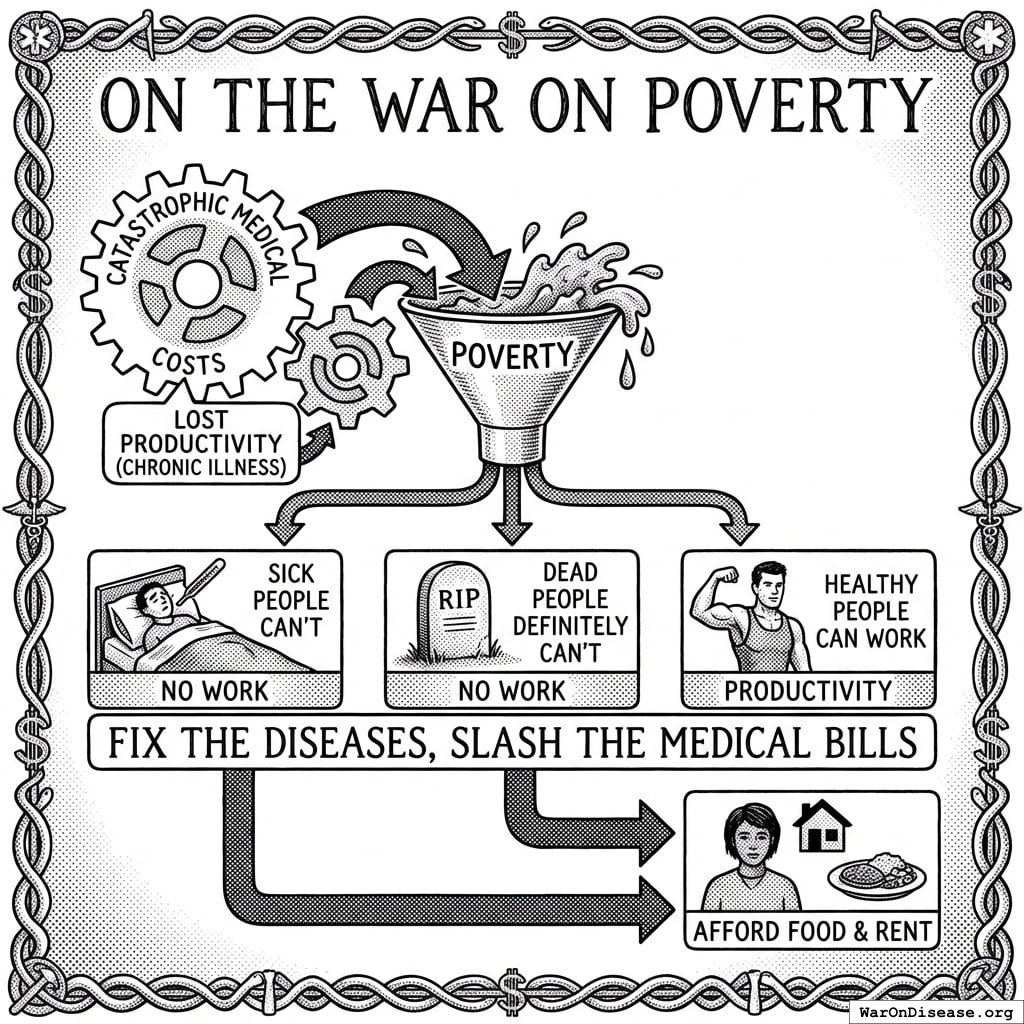

On the War on Poverty

A huge portion of poverty is driven by catastrophic medical costs and lost productivity from chronic illness.

Healthy people can work. Sick people can’t. Dead people definitely can’t. This shouldn’t be controversial, yet here we are having to explain it.

Fix the diseases, slash the medical bills, and suddenly people can afford food and rent.

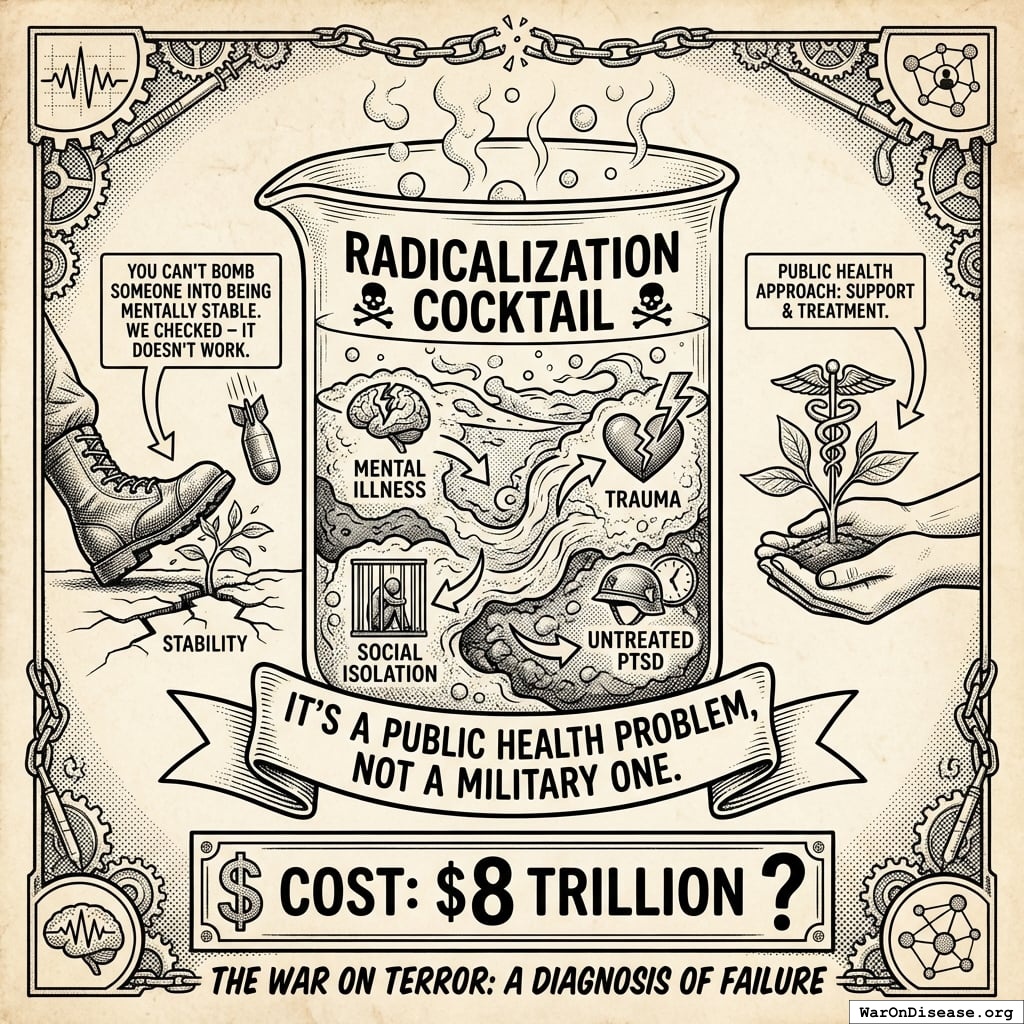

On the War on Terror

Radicalization is often a cocktail of mental illness, trauma, social isolation, and untreated PTSD.

It’s a public health problem, not a military one. You can’t bomb someone into being mentally stable. We checked - it doesn’t work. Cost $8 trillion though.

On the War on Crime

A vast amount of crime is linked to addiction, personality disorders, impulse control issues, and even environmental factors like lead poisoning.

If you fix the brain chemistry that makes people violent and impulsive, crime rates plummet. But that would put a lot of prisons out of business, and we can’t have that.

On The Obvious Truth Nobody Wants to Admit:

Fix the biology, and you fix the society.

It’s not a panacea. Difficult people will remain difficult. But you’ll have healthy, functional difficult people instead of sick, desperate ones, which is a measurable improvement.

And it’s definitely more effective than building more prisons and dropping more bombs, which is what we’ve been doing for the past century with mixed results at best.

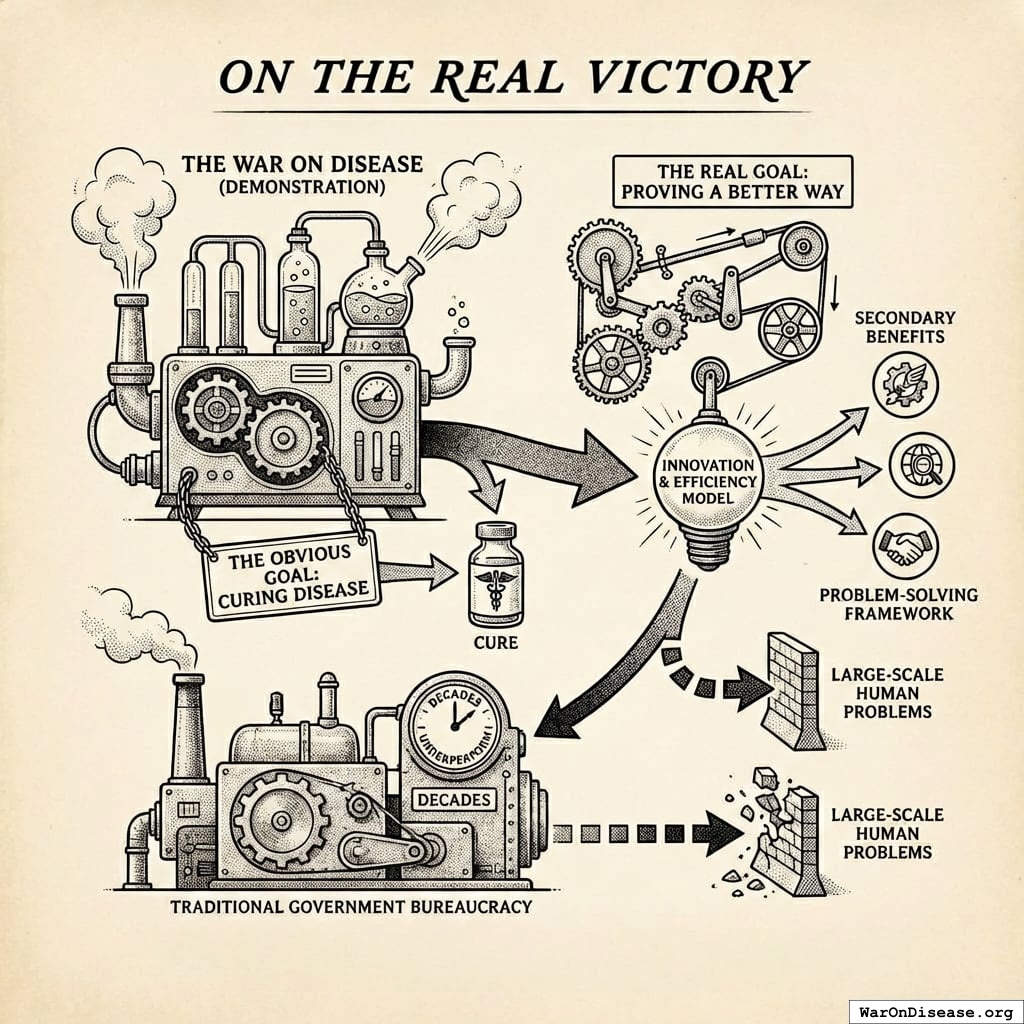

On The Real Victory

The War on Disease is a demonstration with secondary benefits.

The obvious goal is curing disease. That’s what it says on the label.

The real goal is proving that there’s a better way to solve large-scale human problems than building a government bureaucracy, giving it a budget, and waiting for it to underperform over several decades.

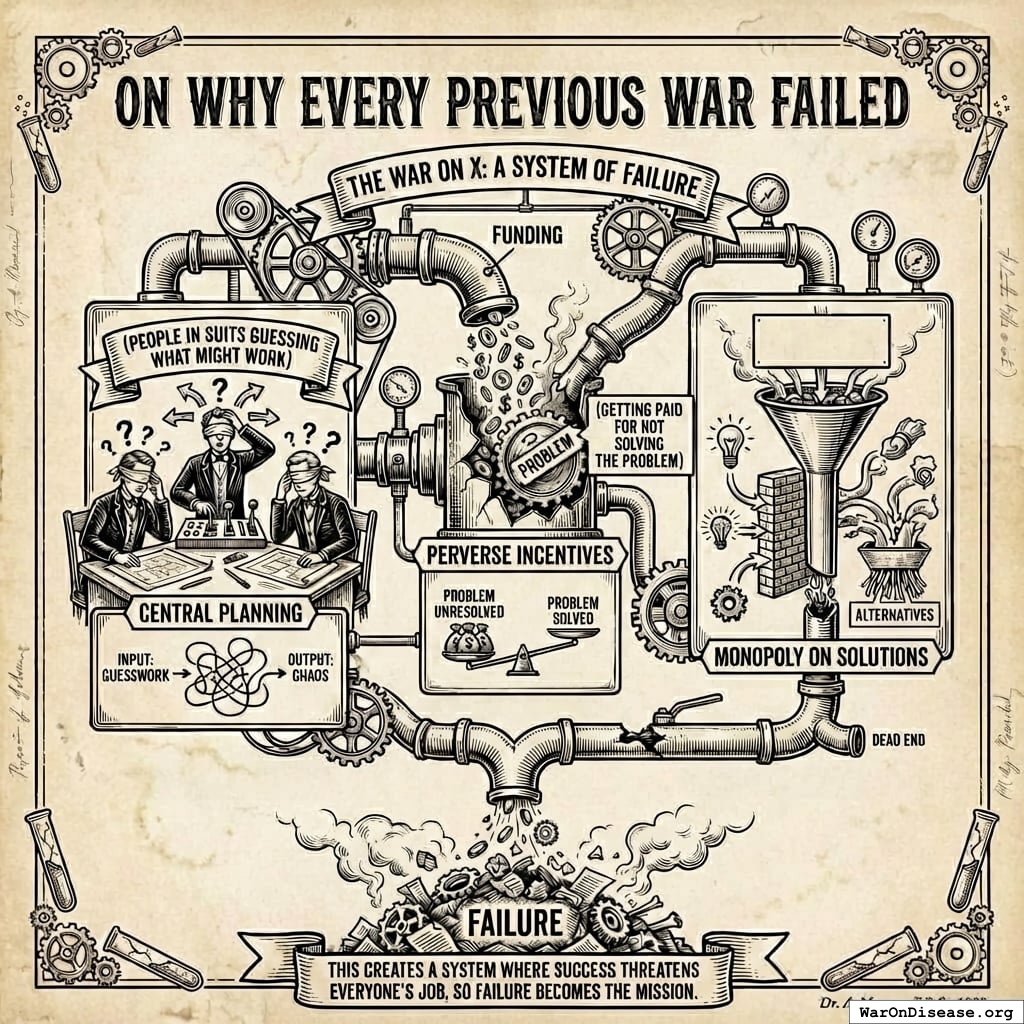

On Why Every Previous War Failed

Every government “War on X” has been a disaster because it was built on:

- Central planning (people in suits guessing what might work)

- Perverse incentives (getting paid for not solving the problem)

- Monopoly on solutions (one approved way to fail)

This creates a system where success threatens everyone’s job, so failure becomes the mission.

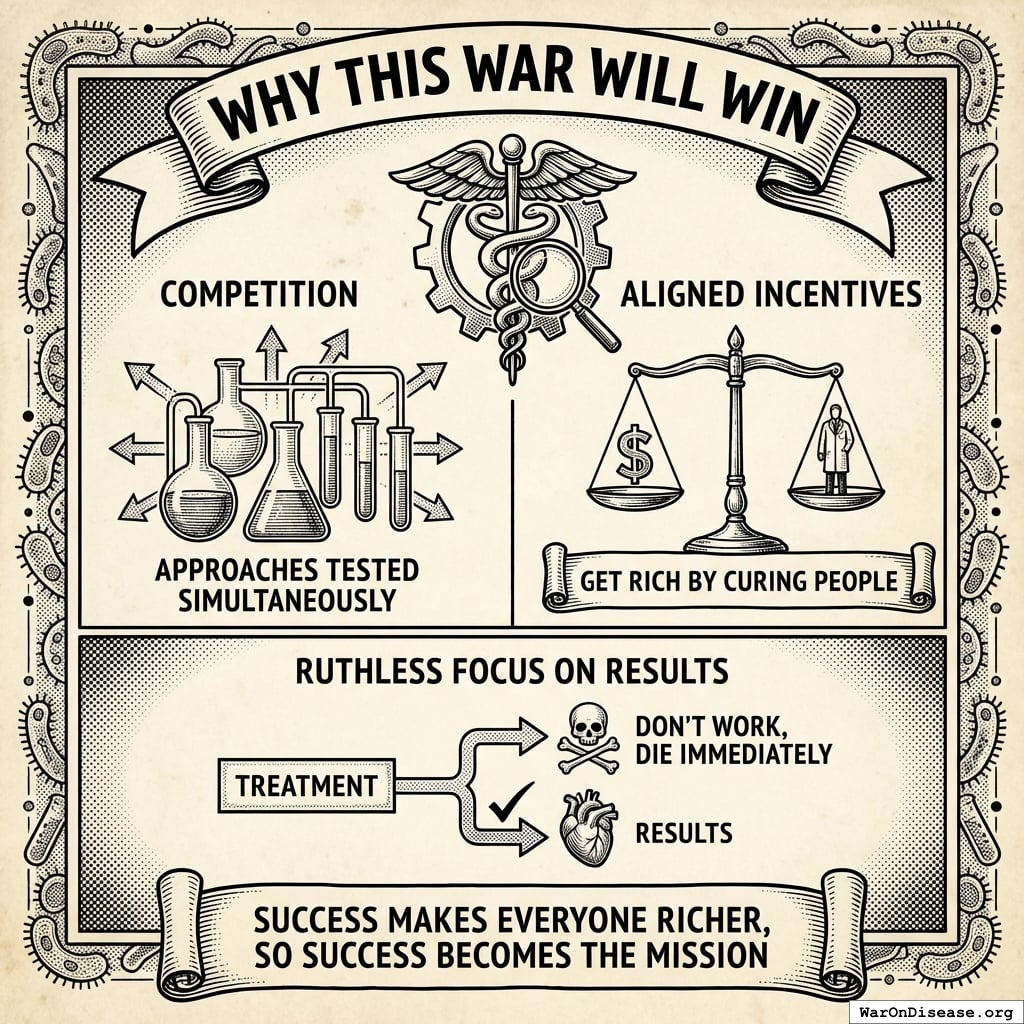

On Why This War Will Win

The War on Disease will be the first government “War on X” to actually win because it’s built on:

- Competition (thousands of approaches tested simultaneously)

- Aligned incentives (you get rich by actually curing people)

- Ruthless focus on results (treatments that don’t work die immediately)

Success makes everyone richer, so success becomes the mission.

On The Part Where Everything Else Gets Fixed:

When this model succeeds, and it will, because mathematics, the credibility of central planning will be notably diminished.

The public will look at the War on Disease and say “wait, why don’t we do this for education? And energy? And other things?”

And bureaucrats will say “because we need to study it first” and people will say “we’re doing it anyway.”

The War on Disease isn’t just the first war you’ll win.

It’s the last war you’ll need to fight, because it gives you a template for solving everything else.

Or to put it another way: You’re not just curing diseases. You’re demonstrating an alternative to government’s habitual approach to failure.

Which, ironically, might be the most durable problem to address. But if you can do it, everything else follows naturally.

1.

Fund, N. C. NIH pragmatic trials: Minimal funding despite 30x cost advantage.

NIH Common Fund: HCS Research Collaboratory https://commonfund.nih.gov/hcscollaboratory (2025)

The NIH Pragmatic Trials Collaboratory funds trials at **$500K for planning phase, $1M/year for implementation**—a tiny fraction of NIH’s budget. The ADAPTABLE trial cost **$14 million** for **15,076 patients** (= **$929/patient**) versus **$420 million** for a similar traditional RCT (30x cheaper), yet pragmatic trials remain severely underfunded. PCORnet infrastructure enables real-world trials embedded in healthcare systems, but receives minimal support compared to basic research funding. Additional sources: https://commonfund.nih.gov/hcscollaboratory | https://pcornet.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/ADAPTABLE_Lay_Summary_21JUL2025.pdf | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5604499/

.

2.

NIH. Antidepressant clinical trial exclusion rates.

Zimmerman et al. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26276679/ (2015)

Mean exclusion rate: 86.1% across 158 antidepressant efficacy trials (range: 44.4% to 99.8%) More than 82% of real-world depression patients would be ineligible for antidepressant registration trials Exclusion rates increased over time: 91.4% (2010-2014) vs. 83.8% (1995-2009) Most common exclusions: comorbid psychiatric disorders, age restrictions, insufficient depression severity, medical conditions Emergency psychiatry patients: only 3.3% eligible (96.7% excluded) when applying 9 common exclusion criteria Only a minority of depressed patients seen in clinical practice are likely to be eligible for most AETs Note: Generalizability of antidepressant trials has decreased over time, with increasingly stringent exclusion criteria eliminating patients who would actually use the drugs in clinical practice Additional sources: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26276679/ | https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26164052/ | https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/news/antidepressant-trials-exclude-most-real-world-patients-with-depression

.

3.

CNBC. Warren buffett’s career average investment return.

CNBC https://www.cnbc.com/2025/05/05/warren-buffetts-return-tally-after-60-years-5502284percent.html (2025)

Berkshire’s compounded annual return from 1965 through 2024 was 19.9%, nearly double the 10.4% recorded by the S&P 500. Berkshire shares skyrocketed 5,502,284% compared to the S&P 500’s 39,054% rise during that period. Additional sources: https://www.cnbc.com/2025/05/05/warren-buffetts-return-tally-after-60-years-5502284percent.html | https://www.slickcharts.com/berkshire-hathaway/returns

.

4.

Group, E. W. US farm subsidy database and analysis.

Environmental Working Group https://farm.ewg.org/ (2024)

US agricultural subsidies total approximately $30 billion annually, but create much larger economic distortions. Top 10% of farms receive 78% of subsidies, benefits concentrated in commodity crops (corn, soy, wheat, cotton), environmental damage from monoculture incentivized, and overall deadweight loss estimated at $50-120 billion annually. Additional sources: https://farm.ewg.org/ | https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/farm-economy/farm-sector-income-finances/government-payments-the-safety-net/

.

5.

Posen, B. R.

Restraint: A New Foundation for u.s. Grand Strategy. (Posen, 2014).

The United States could maintain adequate deterrence and defense with a much smaller military budget. Current spending levels reflect force projection capabilities far beyond what homeland security and deterrence require. A strategy of restraint could reduce defense spending by 40-50% while maintaining security through nuclear deterrence and geographic advantages. Additional sources: https://www.cornellpress.cornell.edu/book/9780801452581/restraint/

.

6.

Alliance, D. P.

The drug war by the numbers. (2021)

Since 1971, the war on drugs has cost the United States an estimated $1 trillion in enforcement. The federal drug control budget was $41 billion in 2022. Mass incarceration costs the U.S. at least $182 billion every year, with over $450 billion spent to incarcerate individuals on drug charges in federal prisons.

8.

Fund, I. M.

IMF fossil fuel subsidies data: 2023 update. (2023)

Globally, fossil fuel subsidies were $7 trillion in 2022 or 7.1 percent of GDP. The United States subsidies totaled $649 billion. Underpricing for local air pollution costs and climate damages are the largest contributor, accounting for about 30 percent each.

9.

Papanicolas, I. et al. Health care spending in the united states and other high-income countries.

Papanicolas et al. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/2674671 (2018)

The US spent approximately twice as much as other high-income countries on medical care (mean per capita: $9,892 vs $5,289), with similar utilization but much higher prices. Administrative costs accounted for 8% of US spending vs 1-3% in other countries. US spending on pharmaceuticals was $1,443 per capita vs $749 elsewhere. Despite spending more, US health outcomes are not better. Additional sources: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/2674671

.

10.

Hsieh, C.-T. & Moretti, E. Housing constraints and spatial misallocation.

Hsieh & Moretti https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/mac.20170388 (2019)

We quantify the amount of spatial misallocation of labor across US cities and its aggregate costs. Tight land-use restrictions in high-productivity cities like New York, San Francisco, and Boston lowered aggregate US growth by 36% from 1964 to 2009. Local constraints on housing supply have had enormous effects on the national economy. Additional sources: https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/mac.20170388

.

11.

Justice, V. I. of. The economic burden of incarceration in the united states.

Vera Institute https://www.vera.org/publications/the-economic-burden-of-incarceration-in-the-u-s (2024)

US incarceration costs approximately $80 billion annually in direct correctional expenditures alone. Including social costs (lost earnings, family impacts, health effects, reduced child outcomes), total burden exceeds $300 billion annually. The US incarcerates at 5x the rate of other OECD countries with no corresponding reduction in crime. Evidence shows community-based alternatives cost less and reduce recidivism more effectively. Additional sources: https://www.vera.org/publications/the-economic-burden-of-incarceration-in-the-u-s | https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2024.html | https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA108-3.html

.

12.

Marron Institute, N. Transit costs project - why US infrastructure costs so much.

NYU Transit Costs Project https://transitcosts.com/ (2024)

The United States builds transit infrastructure at dramatically higher costs than peer countries. New York’s Second Avenue Subway cost $2.5 billion per kilometer vs. $200-500 million in European cities. US highway construction similarly costs 2-5x more than comparable projects abroad. Causes include: excessive environmental review, litigation risk, lack of in-house expertise, fragmented project management, and inflated soft costs. Additional sources: https://transitcosts.com/ | https://www.brookings.edu/articles/why-does-infrastructure-cost-so-much/

.

13.

Clemens, M. A.

Economics and emigration: Trillion-dollar bills on the sidewalk? Journal of Economic Perspectives 25, 83–106 (2011)

Free global labor mobility would increase gross world product by somewhere in the range of 67-147%... The gains to eliminating migration barriers amount to large fractions of world GDP—one or two orders of magnitude larger than the gains from dropping all remaining restrictions on international flows of goods and capital.

16.

Foundation, T. Tax compliance costs the US economy $546 billion annually.

https://taxfoundation.org/data/all/federal/irs-tax-compliance-costs/ (2024)

Americans will spend over 7.9 billion hours complying with IRS tax filing and reporting requirements in 2024. This costs the economy roughly $413 billion in lost productivity. In addition, the IRS estimates that Americans spend roughly $133 billion annually in out-of-pocket costs, bringing the total compliance costs to $546 billion, or nearly 2 percent of GDP.

17.

Organization, W. H. WHO global health estimates 2024.

World Health Organization https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates (2024)

Comprehensive mortality and morbidity data by cause, age, sex, country, and year Global mortality: 55-60 million deaths annually Lives saved by modern medicine (vaccines, cardiovascular drugs, oncology): 12M annually (conservative aggregate) Leading causes of death: Cardiovascular disease (17.9M), Cancer (10.3M), Respiratory disease (4.0M) Note: Baseline data for regulatory mortality analysis. Conservative estimate of pharmaceutical impact based on WHO immunization data (4.5M/year from vaccines) + cardiovascular interventions (3.3M/year) + oncology (1.5M/year) + other therapies. Additional sources: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates

.

18.

GiveWell. GiveWell cost per life saved for top charities (2024).

GiveWell: Top Charities https://www.givewell.org/charities/top-charities General range: $3,000-$5,500 per life saved (GiveWell top charities) Helen Keller International (Vitamin A): $3,500 average (2022-2024); varies $1,000-$8,500 by country Against Malaria Foundation: $5,500 per life saved New Incentives (vaccination incentives): $4,500 per life saved Malaria Consortium (seasonal malaria chemoprevention): $3,500 per life saved VAS program details: $2 to provide vitamin A supplements to child for one year Note: Figures accurate for 2024. Helen Keller VAS program has wide country variation ($1K-$8.5K) but $3,500 is accurate average. Among most cost-effective interventions globally Additional sources: https://www.givewell.org/charities/top-charities | https://www.givewell.org/charities/helen-keller-international | https://ourworldindata.org/cost-effectiveness

.

19.

AARP. Unpaid caregiver hours and economic value.

AARP 2023 https://www.aarp.org/caregiving/financial-legal/info-2023/unpaid-caregivers-provide-billions-in-care.html (2023)

Average family caregiver: 25-26 hours per week (100-104 hours per month) 38 million caregivers providing 36 billion hours of care annually Economic value: $16.59 per hour = $600 billion total annual value (2021) 28% of people provided eldercare on a given day, averaging 3.9 hours when providing care Caregivers living with care recipient: 37.4 hours per week Caregivers not living with recipient: 23.7 hours per week Note: Disease-related caregiving is subset of total; includes elderly care, disability care, and child care Additional sources: https://www.aarp.org/caregiving/financial-legal/info-2023/unpaid-caregivers-provide-billions-in-care.html | https://www.bls.gov/news.release/elcare.nr0.htm | https://www.caregiver.org/resource/caregiver-statistics-demographics/

.

20.

MMWR, C. Childhood vaccination economic benefits.

CDC MMWR https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/73/wr/mm7331a2.htm (1994)

US programs (1994-2023): $540B direct savings, $2.7T societal savings ( $18B/year direct, $90B/year societal) Global (2001-2020): $820B value for 10 diseases in 73 countries ( $41B/year) ROI: $11 return per $1 invested Measles vaccination alone saved 93.7M lives (61% of 154M total) over 50 years (1974-2024) Additional sources: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/73/wr/mm7331a2.htm | https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(24

.

22.

Labor Statistics, U. S. B. of.

CPI inflation calculator. (2024)

CPI-U (1980): 82.4 CPI-U (2024): 313.5 Inflation multiplier (1980-2024): 3.80× Cumulative inflation: 280.48% Average annual inflation rate: 3.08% Note: Official U.S. government inflation data using Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U). Additional sources: https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm

.

23.

Del Rosal, I. The empirical measurement of rent-seeking costs.

Journal of Economic Surveys https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1467-6419.2009.00621.x (2011)

A comprehensive survey of empirical estimates finds rent-seeking costs range from 0.2% to 23.7% of GDP across different methodologies and countries. Laband & Sophocleus (1988) estimated up to 45% for the US.

24.

via, D. analysis. ClinicalTrials.gov cumulative enrollment data (2025).

Direct analysis via ClinicalTrials.gov API v2 https://clinicaltrials.gov/data-api/api Analysis of 100,000 active/recruiting/completed trials on ClinicalTrials.gov (November 2025) shows cumulative enrollment of 12.2 million participants: Phase 1 (722k), Phase 2 (2.2M), Phase 3 (6.5M), Phase 4 (2.7M). Median participants per trial: Phase 1 (33), Phase 2 (60), Phase 3 (237), Phase 4 (90). Additional sources: https://clinicaltrials.gov/data-api/api

.

25.

CAN, A. Clinical trial patient participation rate.

ACS CAN: Barriers to Clinical Trial Enrollment https://www.fightcancer.org/policy-resources/barriers-patient-enrollment-therapeutic-clinical-trials-cancer Only 3-5% of adult cancer patients in US receive treatment within clinical trials About 5% of American adults have ever participated in any clinical trial Oncology: 2-3% of all oncology patients participate Contrast: 50-60% enrollment for pediatric cancer trials (<15 years old) Note: 20% of cancer trials fail due to insufficient enrollment; 11% of research sites enroll zero patients Additional sources: https://www.fightcancer.org/policy-resources/barriers-patient-enrollment-therapeutic-clinical-trials-cancer | https://hints.cancer.gov/docs/Briefs/HINTS_Brief_48.pdf

.

26.

ScienceDaily. Global prevalence of chronic disease.

ScienceDaily: GBD 2015 Study https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2015/06/150608081753.htm (2015)

2.3 billion individuals had more than five ailments (2013) Chronic conditions caused 74% of all deaths worldwide (2019), up from 67% (2010) Approximately 1 in 3 adults suffer from multiple chronic conditions (MCCs) Risk factor exposures: 2B exposed to biomass fuel, 1B to air pollution, 1B smokers Projected economic cost: $47 trillion by 2030 Note: 2.3B with 5+ ailments is more accurate than "2B with chronic disease." One-third of all adults globally have multiple chronic conditions Additional sources: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2015/06/150608081753.htm | https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10830426/ | https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6214883/

.

27.

C&EN. Annual number of new drugs approved globally: 50.

C&EN https://cen.acs.org/pharmaceuticals/50-new-drugs-received-FDA/103/i2 (2025)

50 new drugs approved annually Additional sources: https://cen.acs.org/pharmaceuticals/50-new-drugs-received-FDA/103/i2 | https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs/novel-drug-approvals-fda

.

28.

estimates, I. Clinical trial abandonment.

Average: 10% abandoned before completion

.

32.

GiveWell. Cost per DALY for deworming programs.

https://www.givewell.org/international/technical/programs/deworming/cost-effectiveness Schistosomiasis treatment: $28.19-$70.48 per DALY (using arithmetic means with varying disability weights) Soil-transmitted helminths (STH) treatment: $82.54 per DALY (midpoint estimate) Note: GiveWell explicitly states this 2011 analysis is "out of date" and their current methodology focuses on long-term income effects rather than short-term health DALYs Additional sources: https://www.givewell.org/international/technical/programs/deworming/cost-effectiveness

.

33.

Numbers, T. by. Pre-1962 drug development costs and timeline (think by numbers).

Think by Numbers: How Many Lives Does FDA Save? https://thinkbynumbers.org/health/how-many-net-lives-does-the-fda-save/ (1962)

Historical estimates (1970-1985): USD $226M fully capitalized (2011 prices) 1980s drugs: $65M after-tax R&D (1990 dollars), $194M compounded to approval (1990 dollars) Modern comparison: $2-3B costs, 7-12 years (dramatic increase from pre-1962) Context: 1962 regulatory clampdown reduced new treatment production by 70%, dramatically increasing development timelines and costs Note: Secondary source; less reliable than Congressional testimony Additional sources: https://thinkbynumbers.org/health/how-many-net-lives-does-the-fda-save/ | https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cost_of_drug_development | https://www.statnews.com/2018/10/01/changing-1962-law-slash-drug-prices/

.

34.

(BIO), B. I. O. BIO clinical development success rates 2011-2020.

Biotechnology Innovation Organization (BIO) https://go.bio.org/rs/490-EHZ-999/images/ClinicalDevelopmentSuccessRates2011_2020.pdf (2021)

Phase I duration: 2.3 years average Total time to market (Phase I-III + approval): 10.5 years average Phase transition success rates: Phase I→II: 63.2%, Phase II→III: 30.7%, Phase III→Approval: 58.1% Overall probability of approval from Phase I: 12% Note: Largest publicly available study of clinical trial success rates. Efficacy lag = 10.5 - 2.3 = 8.2 years post-safety verification. Additional sources: https://go.bio.org/rs/490-EHZ-999/images/ClinicalDevelopmentSuccessRates2011_2020.pdf

.

35.

Medicine, N. Drug repurposing rate ( 30%).

Nature Medicine https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-024-03233-x (2024)

Approximately 30% of drugs gain at least one new indication after initial approval. Additional sources: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-024-03233-x

.

36.

EPI. Education investment economic multiplier (2.1).

EPI: Public Investments Outside Core Infrastructure https://www.epi.org/publication/bp348-public-investments-outside-core-infrastructure/ Early childhood education: Benefits 12X outlays by 2050; $8.70 per dollar over lifetime Educational facilities: $1 spent → $1.50 economic returns Energy efficiency comparison: 2-to-1 benefit-to-cost ratio (McKinsey) Private return to schooling: 9% per additional year (World Bank meta-analysis) Note: 2.1 multiplier aligns with benefit-to-cost ratios for educational infrastructure/energy efficiency. Early childhood education shows much higher returns (12X by 2050) Additional sources: https://www.epi.org/publication/bp348-public-investments-outside-core-infrastructure/ | https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/442521523465644318/pdf/WPS8402.pdf | https://freopp.org/whitepapers/establishing-a-practical-return-on-investment-framework-for-education-and-skills-development-to-expand-economic-opportunity/

.

37.

PMC. Healthcare investment economic multiplier (1.8).

PMC: California Universal Health Care https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5954824/ (2022)

Healthcare fiscal multiplier: 4.3 (95% CI: 2.5-6.1) during pre-recession period (1995-2007) Overall government spending multiplier: 1.61 (95% CI: 1.37-1.86) Why healthcare has high multipliers: No effect on trade deficits (spending stays domestic); improves productivity & competitiveness; enhances long-run potential output Gender-sensitive fiscal spending (health & care economy) produces substantial positive growth impacts Note: "1.8" appears to be conservative estimate; research shows healthcare multipliers of 4.3 Additional sources: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5954824/ | https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/government-investment-and-fiscal-stimulus | https://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3849102/ | https://set.odi.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Fiscal-multipliers-review.pdf

.

38.

Bank, W. Infrastructure investment economic multiplier (1.6).

World Bank: Infrastructure Investment as Stimulus https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/ppps/effectiveness-infrastructure-investment-fiscal-stimulus-what-weve-learned (2022)

Infrastructure fiscal multiplier: 1.6 during contractionary phase of economic cycle Average across all economic states: 1.5 (meaning $1 of public investment → $1.50 of economic activity) Time horizon: 0.8 within 1 year, 1.5 within 2-5 years Range of estimates: 1.5-2.0 (following 2008 financial crisis & American Recovery Act) Italian public construction: 1.5-1.9 multiplier US ARRA: 0.4-2.2 range (differential impacts by program type) Economic Policy Institute: Uses 1.6 for infrastructure spending (middle range of estimates) Note: Public investment less likely to crowd out private activity during recessions; particularly effective when monetary policy loose with near-zero rates Additional sources: https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/ppps/effectiveness-infrastructure-investment-fiscal-stimulus-what-weve-learned | https://www.gihub.org/infrastructure-monitor/insights/fiscal-multiplier-effect-of-infrastructure-investment/ | https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/government-investment-and-fiscal-stimulus | https://www.richmondfed.org/publications/research/economic_brief/2022/eb_22-04

.

39.

Mercatus. Military spending economic multiplier (0.6).

Mercatus: Defense Spending and Economy https://www.mercatus.org/research/research-papers/defense-spending-and-economy Ramey (2011): 0.6 short-run multiplier Barro (1981): 0.6 multiplier for WWII spending (war spending crowded out 40¢ private economic activity per federal dollar) Barro & Redlick (2011): 0.4 within current year, 0.6 over two years; increased govt spending reduces private-sector GDP portions General finding: $1 increase in deficit-financed federal military spending = less than $1 increase in GDP Variation by context: Central/Eastern European NATO: 0.6 on impact, 1.5-1.6 in years 2-3, gradual fall to zero Ramey & Zubairy (2018): Cumulative 1% GDP increase in military expenditure raises GDP by 0.7% Additional sources: https://www.mercatus.org/research/research-papers/defense-spending-and-economy | https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/world-war-ii-america-spending-deficits-multipliers-and-sacrifice | https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RRA700/RRA739-2/RAND_RRA739-2.pdf

.

40.

FDA. FDA-approved prescription drug products (20,000+).

FDA https://www.fda.gov/media/143704/download There are over 20,000 prescription drug products approved for marketing. Additional sources: https://www.fda.gov/media/143704/download

.

42.

ACLED. Active combat deaths annually.

ACLED: Global Conflict Surged 2024 https://acleddata.com/2024/12/12/data-shows-global-conflict-surged-in-2024-the-washington-post/ (2024)

2024: 233,597 deaths (30% increase from 179,099 in 2023) Deadliest conflicts: Ukraine (67,000), Palestine (35,000) Nearly 200,000 acts of violence (25% higher than 2023, double from 5 years ago) One in six people globally live in conflict-affected areas Additional sources: https://acleddata.com/2024/12/12/data-shows-global-conflict-surged-in-2024-the-washington-post/ | https://acleddata.com/media-citation/data-shows-global-conflict-surged-2024-washington-post | https://acleddata.com/conflict-index/index-january-2024/

.

43.

UCDP. State violence deaths annually.

UCDP: Uppsala Conflict Data Program https://ucdp.uu.se/ Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP): Tracks one-sided violence (organized actors attacking unarmed civilians) UCDP definition: Conflicts causing at least 25 battle-related deaths in calendar year 2023 total organized violence: 154,000 deaths; Non-state conflicts: 20,900 deaths UCDP collects data on state-based conflicts, non-state conflicts, and one-sided violence Specific "2,700 annually" figure for state violence not found in recent UCDP data; actual figures vary annually Additional sources: https://ucdp.uu.se/ | https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uppsala_Conflict_Data_Program | https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/deaths-in-armed-conflicts-by-region

.

44.

Data, O. W. in. Terror attack deaths (8,300 annually).

Our World in Data: Terrorism https://ourworldindata.org/terrorism (2024)

2023: 8,352 deaths (22% increase from 2022, highest since 2017) 2023: 3,350 terrorist incidents (22% decrease), but 56% increase in avg deaths per attack Global Terrorism Database (GTD): 200,000+ terrorist attacks recorded (2021 version) Maintained by: National Consortium for Study of Terrorism & Responses to Terrorism (START), U. of Maryland Geographic shift: Epicenter moved from Middle East to Central Sahel (sub-Saharan Africa) - now >50% of all deaths Additional sources: https://ourworldindata.org/terrorism | https://reliefweb.int/report/world/global-terrorism-index-2024 | https://www.start.umd.edu/gtd/ | https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/fatalities-from-terrorism

.

45.

Health Metrics, I. for & (IHME), E. IHME global burden of disease 2021 (2.88B DALYs, 1.13B YLD).

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/ (2024)

In 2021, global DALYs totaled approximately 2.88 billion, comprising 1.75 billion Years of Life Lost (YLL) and 1.13 billion Years Lived with Disability (YLD). This represents a 13% increase from 2019 (2.55B DALYs), largely attributable to COVID-19 deaths and aging populations. YLD accounts for approximately 39% of total DALYs, reflecting the substantial burden of non-fatal chronic conditions. Additional sources: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/ | https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(24 | https://www.healthdata.org/research-analysis/about-gbd

.

46.

War, B. W. C. of. Environmental cost of war ($100B annually).

Brown Watson Costs of War: Environmental Cost https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/costs/social/environment War on Terror emissions: 1.2B metric tons GHG (equivalent to 257M cars/year) Military: 5.5% of global GHG emissions (2X aviation + shipping combined) US DoD: World’s single largest institutional oil consumer, 47th largest emitter if nation Cleanup costs: $500B+ for military contaminated sites Gaza war environmental damage: $56.4B; landmine clearance: $34.6B expected Climate finance gap: Rich nations spend 30X more on military than climate finance Note: Military activities cause massive environmental damage through GHG emissions, toxic contamination, and long-term cleanup costs far exceeding current climate finance commitments Additional sources: https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/costs/social/environment | https://earth.org/environmental-costs-of-wars/ | https://transformdefence.org/transformdefence/stats/

.

47.

ScienceDaily. Medical research lives saved annually (4.2 million).

ScienceDaily: Physical Activity Prevents 4M Deaths https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2020/06/200617194510.htm (2020)

Physical activity: 3.9M early deaths averted annually worldwide (15% lower premature deaths than without) COVID vaccines (2020-2024): 2.533M deaths averted, 14.8M life-years preserved; first year alone: 14.4M deaths prevented Cardiovascular prevention: 3 interventions could delay 94.3M deaths over 25 years (antihypertensives alone: 39.4M) Pandemic research response: Millions of deaths averted through rapid vaccine/drug development Additional sources: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2020/06/200617194510.htm | https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9537923/ | https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.038160 | https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9464102/

.

48.

SIPRI. 36:1 disparity ratio of spending on weapons over cures.

SIPRI: Military Spending https://www.sipri.org/commentary/blog/2016/opportunity-cost-world-military-spending (2016)

Global military spending: $2.7 trillion (2024, SIPRI) Global government medical research: $68 billion (2024) Actual ratio: 39.7:1 in favor of weapons over medical research Military R&D alone: $85B (2004 data, 10% of global R&D) Military spending increases crowd out health: 1% ↑ military = 0.62% ↓ health spending Note: Ratio actually worse than 36:1. Each 1% increase in military spending reduces health spending by 0.62%, with effect more intense in poorer countries (0.962% reduction) Additional sources: https://www.sipri.org/commentary/blog/2016/opportunity-cost-world-military-spending | https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9174441/ | https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R45403

.

49.

Numbers, T. by. Lost human capital due to war ($270B annually).

Think by Numbers: War Costs $74 <https://thinkbynumbers.org/military/war/the-economic-case-for-peace-a-comprehensive-financial-analysis/> (2021)

Lost human capital from war: $300B annually (economic impact of losing skilled/productive individuals to conflict) Broader conflict/violence cost: $14T/year globally 1.4M violent deaths/year; conflict holds back economic development, causes instability, widens inequality, erodes human capital 2002: 48.4M DALYs lost from 1.6M violence deaths = $151B economic value (2000 USD) Economic toll includes: commodity prices, inflation, supply chain disruption, declining output, lost human capital Additional sources: <https://thinkbynumbers.org/military/war/the-economic-case-for-peace-a-comprehensive-financial-analysis/> | https://www.weforum.org/stories/2021/02/war-violence-costs-each-human-5-a-day/ | https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19115548/

.

50.

PubMed. Psychological impact of war cost ($100B annually).

PubMed: Economic Burden of PTSD https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35485933/ PTSD economic burden (2018 U.S.): $232.2B total ($189.5B civilian, $42.7B military) Civilian costs driven by: Direct healthcare ($66B), unemployment ($42.7B) Military costs driven by: Disability ($17.8B), direct healthcare ($10.1B) Exceeds costs of other mental health conditions (anxiety, depression) War-exposed populations: 2-3X higher rates of anxiety, depression, PTSD; women and children most vulnerable Note: Actual burden $232B, significantly higher than "$100B" claimed Additional sources: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35485933/ | https://news.va.gov/103611/study-national-economic-burden-of-ptsd-staggering/ | https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9957523/

.

51.

CGDev. UNHCR average refugee support cost.

CGDev https://www.cgdev.org/blog/costs-hosting-refugees-oecd-countries-and-why-uk-outlier (2024)

The average cost of supporting a refugee is $1,384 per year. This represents total host country costs (housing, healthcare, education, security). OECD countries average $6,100 per refugee (mean 2022-2023), with developing countries spending $700-1,000. Global weighted average of $1,384 is reasonable given that 75-85% of refugees are in low/middle-income countries. Additional sources: https://www.cgdev.org/blog/costs-hosting-refugees-oecd-countries-and-why-uk-outlier | https://www.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/2024-11/UNHCR-WB-global-cost-of-refugee-inclusion-in-host-country-health-systems.pdf

.

52.

Bank, W. World bank trade disruption cost from conflict.

World Bank https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/trade/publication/trading-away-from-conflict Estimated $616B annual cost from conflict-related trade disruption. World Bank research shows civil war costs an average developing country 30 years of GDP growth, with 20 years needed for trade to return to pre-war levels. Trade disputes analysis shows tariff escalation could reduce global exports by up to $674 billion. Additional sources: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/trade/publication/trading-away-from-conflict | https://www.nber.org/papers/w11565 | http://blogs.worldbank.org/en/trade/impacts-global-trade-and-income-current-trade-disputes

.

53.

VA. Veteran healthcare cost projections.

VA https://department.va.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/2026-Budget-in-Brief.pdf (2026)

VA budget: $441.3B requested for FY 2026 (10% increase). Disability compensation: $165.6B in FY 2024 for 6.7M veterans. PACT Act projected to increase spending by $300B between 2022-2031. Costs under Toxic Exposures Fund: $20B (2024), $30.4B (2025), $52.6B (2026). Additional sources: https://department.va.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/2026-Budget-in-Brief.pdf | https://www.cbo.gov/publication/45615 | https://www.legion.org/information-center/news/veterans-healthcare/2025/june/va-budget-tops-400-billion-for-2025-from-higher-spending-on-mandated-benefits-medical-care

.

55.

size, D. from global market & ratios, public/private funding. Private industry clinical trial spending.

Private pharmaceutical and biotech industry spends approximately $75-90 billion annually on clinical trials, representing roughly 90% of global clinical trial spending.

56.

IHME Global Burden of Disease (2.55B DALYs), C. from & GDP per capita valuation, global. $109 trillion annual global disease burden.

The global economic burden of disease, including direct healthcare costs (\(8.2 trillion) and lost productivity (\)100.9 trillion from 2.55 billion DALYs × \(39,570 per DALY), totals approximately\)109.1 trillion annually.

57.

Trials, A. C. Global government spending on interventional clinical trials: $3-6 billion/year.

Applied Clinical Trials https://www.appliedclinicaltrialsonline.com/view/sizing-clinical-research-market Estimated range based on NIH ( $0.8-5.6B), NIHR ($1.6B total budget), and EU funding ( $1.3B/year). Roughly 5-10% of global market. Additional sources: https://www.appliedclinicaltrialsonline.com/view/sizing-clinical-research-market | https://www.thelancet.com/journals/langlo/article/PIIS2214-109X(20

.

58.

Suisse/UBS, C. Credit suisse global wealth report 2023.

Credit Suisse/UBS https://www.ubs.com/global/en/family-office-uhnw/reports/global-wealth-report-2023.html (2023)

Total global household wealth: USD 454.4 trillion (2022) Wealth declined by USD 11.3 trillion (-2.4%) in 2022, first decline since 2008 Wealth per adult: USD 84,718 Additional sources: https://www.ubs.com/global/en/family-office-uhnw/reports/global-wealth-report-2023.html

.

59.

budgets:, S. component country. Global government medical research spending ($67.5B, 2023–2024).

See component country budgets: NIH Budget #nih-budget-fy2025.

61.

budgets, E. from major foundation & activities. Nonprofit clinical trial funding estimate.

Nonprofit foundations spend an estimated $2-5 billion annually on clinical trials globally, representing approximately 2-5% of total clinical trial spending.

62.

IQVIA, I. reports: Global pharmaceutical r&d spending.

Total global pharmaceutical R&D spending is approximately $300 billion annually. Clinical trials represent 15-20% of this total ($45-60B), with the remainder going to drug discovery, preclinical research, regulatory affairs, and manufacturing development.

63.

UN. Global population reaches 8 billion.

UN: World Population 8 Billion Nov 15 2022 https://www.un.org/en/desa/world-population-reach-8-billion-15-november-2022 (2022)

Milestone: November 15, 2022 (UN World Population Prospects 2022) Day of Eight Billion" designated by UN Added 1 billion people in just 11 years (2011-2022) Growth rate: Slowest since 1950; fell under 1% in 2020 Future: 15 years to reach 9B (2037); projected peak 10.4B in 2080s Projections: 8.5B (2030), 9.7B (2050), 10.4B (2080-2100 plateau) Note: Milestone reached Nov 2022. Population growth slowing; will take longer to add next billion (15 years vs 11 years) Additional sources: https://www.un.org/en/desa/world-population-reach-8-billion-15-november-2022 | https://www.un.org/en/dayof8billion | https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Day_of_Eight_Billion

.

64.

School, H. K. 3.5% participation tipping point.

Harvard Kennedy School https://www.hks.harvard.edu/centers/carr/publications/35-rule-how-small-minority-can-change-world (2020)

The research found that nonviolent campaigns were twice as likely to succeed as violent ones, and once 3.5% of the population were involved, they were always successful. Chenoweth and Maria Stephan studied the success rates of civil resistance efforts from 1900 to 2006, finding that nonviolent movements attracted, on average, four times as many participants as violent movements and were more likely to succeed. Key finding: Every campaign that mobilized at least 3.5% of the population in sustained protest was successful (in their 1900-2006 dataset) Note: The 3.5% figure is a descriptive statistic from historical analysis, not a guaranteed threshold. One exception (Bahrain 2011-2014 with 6%+ participation) has been identified. The rule applies to regime change, not policy change in democracies. Additional sources: https://www.hks.harvard.edu/centers/carr/publications/35-rule-how-small-minority-can-change-world | https://www.hks.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/2024-05/Erica%20Chenoweth_2020-005.pdf | https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20190513-it-only-takes-35-of-people-to-change-the-world | https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/3.5%25_rule

.

65.

NHGRI. Human genome project and CRISPR discovery.

NHGRI https://www.genome.gov/11006929/2003-release-international-consortium-completes-hgp (2003)

Your DNA is 3 billion base pairs Read the entire code (Human Genome Project, completed 2003) Learned to edit it (CRISPR, discovered 2012) Additional sources: https://www.genome.gov/11006929/2003-release-international-consortium-completes-hgp | https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/2020/press-release/

.

66.

PMC. Only 12% of human interactome targeted.

PMC https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10749231/ (2023)

Mapping 350,000+ clinical trials showed that only 12% of the human interactome has ever been targeted by drugs. Additional sources: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10749231/

.

67.

WHO. ICD-10 code count ( 14,000).

WHO https://icd.who.int/browse10/2019/en (2019)

The ICD-10 classification contains approximately 14,000 codes for diseases, signs and symptoms. Additional sources: https://icd.who.int/browse10/2019/en

.

68.

Wikipedia. Longevity escape velocity (LEV) - maximum human life extension potential.

Wikipedia: Longevity Escape Velocity https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Longevity_escape_velocity Longevity escape velocity: Hypothetical point where medical advances extend life expectancy faster than time passes Term coined by Aubrey de Grey (biogerontologist) in 2004 paper; concept from David Gobel (Methuselah Foundation) Current progress: Science adds 3 months to lifespan per year; LEV requires adding >1 year per year Sinclair (Harvard): "There is no biological upper limit to age" - first person to live to 150 may already be born De Grey: 50% chance of reaching LEV by mid-to-late 2030s; SENS approach = damage repair rather than slowing damage Kurzweil (2024): LEV by 2029-2035, AI will simulate biological processes to accelerate solutions George Church: LEV "in a decade or two" via age-reversal clinical trials Natural lifespan cap: 120-150 years (Jeanne Calment record: 122); engineering approach could bypass via damage repair Key mechanisms: Epigenetic reprogramming, senolytic drugs, stem cell therapy, gene therapy, AI-driven drug discovery Current record: Jeanne Calment (122 years, 164 days) - record unbroken since 1997 Note: LEV is theoretical but increasingly plausible given demonstrated age reversal in mice (109% lifespan extension) and human cells (30-year epigenetic age reversal) Additional sources: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Longevity_escape_velocity | https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC423155/ | https://www.popularmechanics.com/science/a36712084/can-science-cure-death-longevity/ | https://www.diamandis.com/blog/longevity-escape-velocity

.

69.

OpenSecrets. Lobbyist statistics for washington d.c.

OpenSecrets: Lobbying in US https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lobbying_in_the_United_States Registered lobbyists: Over 12,000 (some estimates); 12,281 registered (2013) Former government employees as lobbyists: 2,200+ former federal employees (1998-2004), including 273 former White House staffers, 250 former Congress members & agency heads Congressional revolving door: 43% (86 of 198) lawmakers who left 1998-2004 became lobbyists; currently 59% leaving to private sector work for lobbying/consulting firms/trade groups Executive branch: 8% were registered lobbyists at some point before/after government service Additional sources: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lobbying_in_the_United_States | https://www.opensecrets.org/revolving-door | https://www.citizen.org/article/revolving-congress/ | https://www.propublica.org/article/we-found-a-staggering-281-lobbyists-whove-worked-in-the-trump-administration

.

70.

Vaccines, M. Measles vaccination ROI.

MDPI Vaccines https://www.mdpi.com/2076-393X/12/11/1210 (2024)

Single measles vaccination: 167:1 benefit-cost ratio. MMR (measles-mumps-rubella) vaccination: 14:1 ROI. Historical US elimination efforts (1966-1974): benefit-cost ratio of 10.3:1 with net benefits exceeding USD 1.1 billion (1972 dollars, or USD 8.0 billion in 2023 dollars). 2-dose MMR programs show direct benefit/cost ratio of 14.2 with net savings of $5.3 billion, and 26.0 from societal perspectives with net savings of $11.6 billion. Additional sources: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-393X/12/11/1210 | https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14760584.2024.2367451

.

73.

Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases (2024), C. from. Diseases getting first effective treatment each year.

Calculated from Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases (2024) https://ojrd.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13023-024-03398-1 (2024)

Under the current system, approximately 10-15 diseases per year receive their FIRST effective treatment. Calculation: 5% of 7,000 rare diseases ( 350) have FDA-approved treatment, accumulated over 40 years of the Orphan Drug Act = 9 rare diseases/year. Adding 5-10 non-rare diseases that get first treatments yields 10-20 total. FDA approves 50 drugs/year, but many are for diseases that already have treatments (me-too drugs, second-line therapies). Only 15 represent truly FIRST treatments for previously untreatable conditions.

74.

NIH. NIH budget (FY 2025).

NIH https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/organization/budget (2024)

The budget total of \(47.7 billion also includes\)1.412 billion derived from PHS Evaluation financing... Additional sources: https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/organization/budget | https://officeofbudget.od.nih.gov/

.

75.

al., B. et. NIH spending on clinical trials: 3.3%.

Bentley et al. https://www.fiercebiotech.com/biotech/nih-spending-clinical-trials-reached-81b-over-decade (2023)

NIH spent $8.1 billion on clinical trials for approved drugs (2010-2019), representing 3.3% of relevant NIH spending. Additional sources: https://www.fiercebiotech.com/biotech/nih-spending-clinical-trials-reached-81b-over-decade | https://www.fiercebiotech.com/biotech/nih-spending-clinical-trials-reached-81b-over-decade

.

76.

PMC. Standard medical research ROI ($20k-$100k/QALY).

PMC: Cost-effectiveness Thresholds Used by Study Authors https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10114019/ (1990)

Typical cost-effectiveness thresholds for medical interventions in rich countries range from $50,000 to $150,000 per QALY. The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) uses a $100,000-$150,000/QALY threshold for value-based pricing. Between 1990-2021, authors increasingly cited $100,000 (47% by 2020-21) or $150,000 (24% by 2020-21) per QALY as benchmarks for cost-effectiveness. Additional sources: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10114019/ | https://icer.org/our-approach/methods-process/cost-effectiveness-the-qaly-and-the-evlyg/

.

77.

Institute, M. RECOVERY trial 82× cost reduction.

Manhattan Institute: Slow Costly Trials https://manhattan.institute/article/slow-costly-clinical-trials-drag-down-biomedical-breakthroughs RECOVERY trial: $500 per patient ($20M for 48,000 patients = $417/patient) Typical clinical trial: $41,000 median per-patient cost Cost reduction: 80-82× cheaper ($41,000 ÷ $500 ≈ 82×) Efficiency: $50 per patient per answer (10 therapeutics tested, 4 effective) Dexamethasone estimated to save >630,000 lives Additional sources: https://manhattan.institute/article/slow-costly-clinical-trials-drag-down-biomedical-breakthroughs | https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9293394/

.

78.

Trials. Patient willingness to participate in clinical trials.

Trials: Patients’ Willingness Survey https://trialsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13063-015-1105-3 Recent surveys: 49-51% willingness (2020-2022) - dramatic drop from 85% (2019) during COVID-19 pandemic Cancer patients when approached: 88% consented to trials (Royal Marsden Hospital) Study type variation: 44.8% willing for drug trial, 76.2% for diagnostic study Top motivation: "Learning more about my health/medical condition" (67.4%) Top barrier: "Worry about experiencing side effects" (52.6%) Additional sources: https://trialsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13063-015-1105-3 | https://www.appliedclinicaltrialsonline.com/view/industry-forced-to-rethink-patient-participation-in-trials | https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7183682/

.

79.

CSDD, T. Cost of drug development.

Various estimates suggest $1.0 - $2.5 billion to bring a new drug from discovery through FDA approval, spread across 10 years. Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development often cited for $1.0 - $2.6 billion/drug. Industry reports (IQVIA, Deloitte) also highlight $2+ billion figures.

80.

Health, V. in. Average lifetime revenue per successful drug.

Value in Health: Sales Revenues for New Therapeutic Agents02754-2/fulltext) https://www.valueinhealthjournal.com/article/S1098-3015(24 Study of 361 FDA-approved drugs from 1995-2014 (median follow-up 13.2 years): Mean lifetime revenue: $15.2 billion per drug Median lifetime revenue: $6.7 billion per drug Revenue after 5 years: $3.2 billion (mean) Revenue after 10 years: $9.5 billion (mean) Revenue after 15 years: $19.2 billion (mean) Distribution highly skewed: top 25 drugs (7%) accounted for 38% of total revenue ($2.1T of $5.5T) Additional sources: https://www.valueinhealthjournal.com/article/S1098-3015(24 | https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1098301524027542

.

81.

Lichtenberg, F. R.

How many life-years have new drugs saved? A three-way fixed-effects analysis of 66 diseases in 27 countries, 2000-2013.

International Health 11, 403–416 (2019)

Using 3-way fixed-effects methodology (disease-country-year) across 66 diseases in 22 countries, this study estimates that drugs launched after 1981 saved 148.7 million life-years in 2013 alone. The regression coefficients for drug launches 0-11 years prior (beta=-0.031, SE=0.008) and 12+ years prior (beta=-0.057, SE=0.013) on years of life lost are highly significant (p<0.0001). Confidence interval for life-years saved: 79.4M-239.8M (95 percent CI) based on propagated standard errors from Table 2.

82.

Deloitte. Pharmaceutical r&d return on investment (ROI).

Deloitte: Measuring Pharmaceutical Innovation 2025 https://www.deloitte.com/ch/en/Industries/life-sciences-health-care/research/measuring-return-from-pharmaceutical-innovation.html (2025)

Deloitte’s annual study of top 20 pharma companies by R&D spend (2010-2024): 2024 ROI: 5.9% (second year of growth after decade of decline) 2023 ROI: 4.3% (estimated from trend) 2022 ROI: 1.2% (historic low since study began, 13-year low) 2021 ROI: 6.8% (record high, inflated by COVID-19 vaccines/treatments) Long-term trend: Declining for over a decade before 2023 recovery Average R&D cost per asset: $2.3B (2022), $2.23B (2024) These returns (1.2-5.9% range) fall far below typical corporate ROI targets (15-20%) Additional sources: https://www.deloitte.com/ch/en/Industries/life-sciences-health-care/research/measuring-return-from-pharmaceutical-innovation.html | https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/deloittes-13th-annual-pharmaceutical-innovation-report-pharma-rd-return-on-investment-falls-in-post-pandemic-market-301738807.html | https://hitconsultant.net/2023/02/16/pharma-rd-roi-falls-to-lowest-level-in-13-years/

.

83.

Discovery, N. R. D. Drug trial success rate from phase i to approval.

Nature Reviews Drug Discovery: Clinical Success Rates https://www.nature.com/articles/nrd.2016.136 (2016)

Overall Phase I to approval: 10-12.8% (conventional wisdom 10%, studies show 12.8%) Recent decline: Average LOA now 6.7% for Phase I (2014-2023 data) Leading pharma companies: 14.3% average LOA (range 8-23%) Varies by therapeutic area: Oncology 3.4%, CNS/cardiovascular lowest at Phase III Phase-specific success: Phase I 47-54%, Phase II 28-34%, Phase III 55-70% Note: 12% figure accurate for historical average. Recent data shows decline to 6.7%, with Phase II as primary attrition point (28% success) Additional sources: https://www.nature.com/articles/nrd.2016.136 | https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6409418/ | https://academic.oup.com/biostatistics/article/20/2/273/4817524

.

84.

SofproMed. Phase 3 cost per trial range.

SofproMed https://www.sofpromed.com/how-much-does-a-clinical-trial-cost Phase 3 clinical trials cost between $20 million and $282 million per trial, with significant variation by therapeutic area and trial complexity. Additional sources: https://www.sofpromed.com/how-much-does-a-clinical-trial-cost | https://www.cbo.gov/publication/57126

.

85.

PMC. Pragmatic trial cost per patient (median $97).

PMC: Costs of Pragmatic Clinical Trials https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6508852/ The median cost per participant was $97 (IQR $19–$478), based on 2015 dollars. Systematic review of 64 embedded pragmatic clinical trials. 25% of trials cost <$19/patient; 10 trials exceeded $1,000/patient. U.S. studies median $187 vs non-U.S. median $27. Additional sources: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6508852/

.

86.

WHO. Polio vaccination ROI.

WHO https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/sustaining-polio-investments-offers-a-high-return (2019)

For every dollar spent, the return on investment is nearly US$ 39." Total investment cost of US$ 7.5 billion generates projected economic and social benefits of US$ 289.2 billion from sustaining polio assets and integrating them into expanded immunization, surveillance and emergency response programmes across 8 priority countries (Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Pakistan, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Yemen). Additional sources: https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/sustaining-polio-investments-offers-a-high-return

.

88.

Hayek, F. A.

The use of knowledge in society.

American Economic Review 35, 519–530 (1945)

The knowledge of the circumstances which we must make use of never exists in concentrated or integrated form but solely as dispersed bits of incomplete and frequently contradictory knowledge which all the separate individuals possess.

89.

Kydland, F. E. & Prescott, E. C.

Rules rather than discretion: The inconsistency of optimal plans.

Journal of Political Economy 85, 473–492 (1977)

Time-inconsistency describes situations where, with the passing of time, policies that were determined to be optimal yesterday are no longer perceived to be optimal today and are not implemented... This insight shifted the focus of policy analysis from the study of individual policy decisions to the design of institutions that mitigate the time consistency problem.

90.

ICRC. International campaign to ban landmines (ICBL) - ottawa treaty (1997).

ICRC https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/resources/documents/article/other/57jpjn.htm (1997)

ICBL: Founded 1992 by 6 NGOs (Handicap International, Human Rights Watch, Medico International, Mines Advisory Group, Physicians for Human Rights, Vietnam Veterans of America Foundation) Started with ONE staff member: Jody Williams as founding coordinator Grew to 1,000+ organizations in 60 countries by 1997 Ottawa Process: 14 months (October 1996 - December 1997) Convention signed by 122 states on December 3, 1997; entered into force March 1, 1999 Achievement: Nobel Peace Prize 1997 (shared by ICBL and Jody Williams) Government funding context: Canada established $100M CAD Canadian Landmine Fund over 10 years (1997); International donors provided $169M in 1997 for mine action (up from $100M in 1996) Additional sources: https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/resources/documents/article/other/57jpjn.htm | https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Campaign_to_Ban_Landmines | https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/1997/summary/ | https://un.org/press/en/1999/19990520.MINES.BRF.html | https://www.the-monitor.org/en-gb/reports/2003/landmine-monitor-2003/mine-action-funding.aspx

.

91.

OpenSecrets.

Revolving door: Former members of congress. (2024)

388 former members of Congress are registered as lobbyists. Nearly 5,400 former congressional staffers have left Capitol Hill to become federal lobbyists in the past 10 years. Additional sources: https://www.opensecrets.org/revolving-door

.

92.

Kinch, M. S. & Griesenauer, R. H.

Lost medicines: A longer view of the pharmaceutical industry with the potential to reinvigorate discovery.

Drug Discovery Today 24, 875–880 (2019)

Research identified 1,600+ medicines available in 1962. The 1950s represented industry high-water mark with >30 new products in five of ten years; this rate would not be replicated until late 1990s. More than half (880) of these medicines were lost following implementation of Kefauver-Harris Amendment. The peak of 1962 would not be seen again until early 21st century. By 2016 number of organizations actively involved in R&D at level not seen since 1914.

93.

Wikipedia. US military spending reduction after WWII.

Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demobilization_of_United_States_Armed_Forces_after_World_War_II (2020)

Peaking at over $81 billion in 1945, the U.S. military budget plummeted to approximately $13 billion by 1948, representing an 84% decrease. The number of personnel was reduced almost 90%, from more than 12 million to about 1.5 million between mid-1945 and mid-1947. Defense spending exceeded 41 percent of GDP in 1945. After World War II, the US reduced military spending to 7.2 percent of GDP by 1948. Defense spending doubled from the 1948 low to 15 percent at the height of the Korean War in 1953. Additional sources: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demobilization_of_United_States_Armed_Forces_after_World_War_II | https://www.americanprogress.org/article/a-historical-perspective-on-military-budgets/ | https://www.stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy/2020/february/war-highest-military-spending-measured | https://www.usgovernmentspending.com/defense_spending_history

.

94.

Baily, M. N. Pre-1962 drug development costs (baily 1972).

Baily (1972) https://samizdathealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/hlthaff.1.2.6.pdf (1972)

Pre-1962: Average cost per new chemical entity (NCE) was $6.5 million (1980 dollars) Inflation-adjusted to 2024 dollars: $6.5M (1980) ≈ $22.5M (2024), using CPI multiplier of 3.46× Real cost increase (inflation-adjusted): $22.5M (pre-1962) → $2,600M (2024) = 116× increase Note: This represents the most comprehensive academic estimate of pre-1962 drug development costs based on empirical industry data Additional sources: https://samizdathealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/hlthaff.1.2.6.pdf

.

95.

Numbers, T. by. Pre-1962 physician-led clinical trials.

Think by Numbers: How Many Lives Does FDA Save? https://thinkbynumbers.org/health/how-many-net-lives-does-the-fda-save/ (1966)

Pre-1962: Physicians could report real-world evidence directly 1962 Drug Amendments replaced "premarket notification" with "premarket approval", requiring extensive efficacy testing Impact: New regulatory clampdown reduced new treatment production by 70%; lifespan growth declined from 4 years/decade to 2 years/decade Drug Efficacy Study Implementation (DESI): NAS/NRC evaluated 3,400+ drugs approved 1938-1962 for safety only; reviewed >3,000 products, >16,000 therapeutic claims FDA has had authority to accept real-world evidence since 1962, clarified by 21st Century Cures Act (2016) Note: Specific "144,000 physicians" figure not verified in sources Additional sources: https://thinkbynumbers.org/health/how-many-net-lives-does-the-fda-save/ | https://www.fda.gov/drugs/enforcement-activities-fda/drug-efficacy-study-implementation-desi | http://www.nasonline.org/about-nas/history/archives/collections/des-1966-1969-1.html

.

96.

GAO. 95% of diseases have 0 FDA-approved treatments.

GAO https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-25-106774 (2025)

95% of diseases have no treatment Additional sources: https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-25-106774 | https://globalgenes.org/rare-disease-facts/

.

98.

al., N. E. Á. et. RECOVERY trial global lives saved ( 1 million).

NHS England: 1 Million Lives Saved https://www.england.nhs.uk/2021/03/covid-treatment-developed-in-the-nhs-saves-a-million-lives/ (2021)

Dexamethasone saved 1 million lives worldwide (NHS England estimate, March 2021, 9 months after discovery). UK alone: 22,000 lives saved. Methodology: Águas et al. Nature Communications 2021 estimated 650,000 lives (range: 240,000-1,400,000) for July-December 2020 alone, based on RECOVERY trial mortality reductions (36% for ventilated, 18% for oxygen-only patients) applied to global COVID hospitalizations. June 2020 announcement: Dexamethasone reduced deaths by up to 1/3 (ventilated patients), 1/5 (oxygen patients). Impact immediate: Adopted into standard care globally within hours of announcement. Additional sources: https://www.england.nhs.uk/2021/03/covid-treatment-developed-in-the-nhs-saves-a-million-lives/ | https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-021-21134-2 | https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/news/steroid-has-saved-the-lives-of-one-million-covid-19-patients-worldwide-figures-show | https://www.recoverytrial.net/news/recovery-trial-celebrates-two-year-anniversary-of-life-saving-dexamethasone-result

.

99.

Museum, N. S. 11. M. &.

September 11 attack facts. (2024)

2,977 people were killed in the September 11, 2001 attacks: 2,753 at the World Trade Center, 184 at the Pentagon, and 40 passengers and crew on United Flight 93 in Shanksville, Pennsylvania.

100.

Bank, W. World bank singapore economic data.

World Bank https://data.worldbank.org/country/singapore (2024)

Singapore GDP per capita (2023): $82,000 - among highest in the world Government spending: 15% of GDP (vs US 38%) Life expectancy: 84.1 years (vs US 77.5 years) Singapore demonstrates that low government spending can coexist with excellent outcomes Additional sources: https://data.worldbank.org/country/singapore

.

101.

Fund, I. M.

IMF singapore government spending data. (2024)

Singapore government spending is approximately 15% of GDP This is 23 percentage points lower than the United States (38%) Despite lower spending, Singapore achieves excellent outcomes: - Life expectancy: 84.1 years (vs US 77.5) - Low crime, world-class infrastructure, AAA credit rating Additional sources: https://www.imf.org/en/Countries/SGP

.

102.

Organization, W. H.

WHO life expectancy data by country. (2024)

Life expectancy at birth varies significantly among developed nations: Switzerland: 84.0 years (2023) Singapore: 84.1 years (2023) Japan: 84.3 years (2023) United States: 77.5 years (2023) - 6.5 years below Switzerland, Singapore Global average: 73 years Note: US spends more per capita on healthcare than any other nation, yet achieves lower life expectancy Additional sources: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates/ghe-life-expectancy-and-healthy-life-expectancy

.

104.

PMC. Contribution of smoking reduction to life expectancy gains.

PMC: Benefits Smoking Cessation Longevity https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1447499/ (2012)

Population-level: Up to 14% (9% men, 14% women) of total life expectancy gain since 1960 due to tobacco control efforts Individual cessation benefits: Quitting at age 35 adds 6.9-8.5 years (men), 6.1-7.7 years (women) vs continuing smokers By cessation age: Age 25-34 = 10 years gained; age 35-44 = 9 years; age 45-54 = 6 years; age 65 = 2.0 years (men), 3.7 years (women) Cessation before age 40: Reduces death risk by 90% Long-term cessation: 10+ years yields survival comparable to never smokers, averts 10 years of life lost Recent cessation: <3 years averts 5 years of life lost Additional sources: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1447499/ | https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2012/11_0295.htm | https://www.ajpmonline.org/article/S0749-3797(24 | https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMsa1211128

.

105.

ICER. Value per QALY (standard economic value).

ICER https://icer.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Reference-Case-4.3.25.pdf (2024)

Standard economic value per QALY: $100,000–$150,000. This is the US and global standard willingness-to-pay threshold for interventions that add costs. Dominant interventions (those that save money while improving health) are favorable regardless of this threshold. Additional sources: https://icer.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Reference-Case-4.3.25.pdf

.

106.

GAO. Annual cost of u.s. Sugar subsidies.

GAO: Sugar Program https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-24-106144 Consumer costs: $2.5-3.5 billion per year (GAO estimate) Net economic cost: $1 billion per year 2022: US consumers paid 2X world price for sugar Program costs $3-4 billion/year but no federal budget impact (costs passed directly to consumers via higher prices) Employment impact: 10,000-20,000 manufacturing jobs lost annually in sugar-reliant industries (confectionery, etc.) Multiple studies confirm: Sweetener Users Association ($2.9-3.5B), AEI ($2.4B consumer cost), Beghin & Elobeid ($2.9-3.5B consumer surplus) Additional sources: https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-24-106144 | https://www.heritage.org/agriculture/report/the-us-sugar-program-bad-consumers-bad-agriculture-and-bad-america | https://www.aei.org/articles/the-u-s-spends-4-billion-a-year-subsidizing-stalinist-style-domestic-sugar-production/

.

107.

Bank, W. Swiss military budget as percentage of GDP.

World Bank: Military Expenditure https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.XPND.GD.ZS?locations=CH 2023: 0.70272% of GDP (World Bank) 2024: CHF 5.95 billion official military spending When including militia system costs: 1% GDP (CHF 8.75B) Comparison: Near bottom in Europe; only Ireland, Malta, Moldova spend less (excluding microstates with no armies) Additional sources: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.XPND.GD.ZS?locations=CH | https://www.avenir-suisse.ch/en/blog-defence-spending-switzerland-is-in-better-shape-than-it-seems/ | https://tradingeconomics.com/switzerland/military-expenditure-percent-of-gdp-wb-data.html

.

108.

Bank, W. Switzerland vs. US GDP per capita comparison.

World Bank: Switzerland GDP Per Capita https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?locations=CH 2024 GDP per capita (PPP-adjusted): Switzerland $93,819 vs United States $75,492 Switzerland’s GDP per capita 24% higher than US when adjusted for purchasing power parity Nominal 2024: Switzerland $103,670 vs US $85,810 Additional sources: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?locations=CH | https://tradingeconomics.com/switzerland/gdp-per-capita-ppp | https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/USA/gdp_per_capita_ppp/

.

109.

Economic Co-operation, O. for & Development.

OECD government spending as percentage of GDP. (2024)

OECD government spending data shows significant variation among developed nations: United States: 38.0% of GDP (2023) Switzerland: 35.0% of GDP - 3 percentage points lower than US Singapore: 15.0% of GDP - 23 percentage points lower than US (per IMF data) OECD average: approximately 40% of GDP Additional sources: https://data.oecd.org/gga/general-government-spending.htm

.

110.

Economic Co-operation, O. for & Development.

OECD median household income comparison. (2024)

Median household disposable income varies significantly across OECD nations: United States: $77,500 (2023) Switzerland: $55,000 PPP-adjusted (lower nominal but comparable purchasing power) Singapore: $75,000 PPP-adjusted Additional sources: https://data.oecd.org/hha/household-disposable-income.htm

.

111.

Institute, C. Chance of dying from terrorism statistic.

Cato Institute: Terrorism and Immigration Risk Analysis https://www.cato.org/policy-analysis/terrorism-immigration-risk-analysis Chance of American dying in foreign-born terrorist attack: 1 in 3.6 million per year (1975-2015) Including 9/11 deaths; annual murder rate is 253x higher than terrorism death rate More likely to die from lightning strike than foreign terrorism Note: Comprehensive 41-year study shows terrorism risk is extremely low compared to everyday dangers Additional sources: https://www.cato.org/policy-analysis/terrorism-immigration-risk-analysis | https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/you-re-more-likely-die-choking-be-killed-foreign-terrorists-n715141

.

112.

Wikipedia. Thalidomide scandal: Worldwide cases and mortality.

Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thalidomide_scandal The total number of embryos affected by the use of thalidomide during pregnancy is estimated at 10,000, of whom about 40% died around the time of birth. More than 10,000 children in 46 countries were born with deformities such as phocomelia. Additional sources: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thalidomide_scandal

.

113.

One, P. Health and quality of life of thalidomide survivors as they age.

PLOS One https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0210222 (2019)

Study of thalidomide survivors documenting ongoing disability impacts, quality of life, and long-term health outcomes. Survivors (now in their 60s) continue to experience significant disability from limb deformities, organ damage, and other effects. Additional sources: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0210222

.

115.

NCBI, F. S. via. Trial costs, FDA study.

FDA Study via NCBI https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6248200/ Overall, the 138 clinical trials had an estimated median (IQR) cost of \(19.0 million (\)12.2 million-\(33.1 million)... The clinical trials cost a median (IQR) of\)41,117 (\(31,802-\)82,362) per patient. Additional sources: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6248200/

.

116.

GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators.

Global burden of disease study 2019: Disability weights.

The Lancet 396, 1204–1222 (2020)

Disability weights for 235 health states used in Global Burden of Disease calculations. Weights range from 0 (perfect health) to 1 (death equivalent). Chronic conditions like diabetes (0.05-0.35), COPD (0.04-0.41), depression (0.15-0.66), and cardiovascular disease (0.04-0.57) show substantial variation by severity. Treatment typically reduces disability weights by 50-80 percent for manageable chronic conditions.

117.

WHO. Annual global economic burden of alzheimer’s and other dementias.

WHO: Dementia Fact Sheet https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (2019)

Global cost: $1.3 trillion (2019 WHO-commissioned study) 50% from informal caregivers (family/friends, 5 hrs/day) 74% of costs in high-income countries despite 61% of patients in LMICs $818B (2010) → $1T (2018) → $1.3T (2019) - rapid growth Note: Costs increased 35% from 2010-2015 alone. Informal care represents massive hidden economic burden Additional sources: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia | https://alz-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/alz.12901

.

118.

Oncology, J. Annual global economic burden of cancer.

JAMA Oncology: Global Cost 2020-2050 https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaoncology/fullarticle/2801798 (2020)

2020-2050 projection: $25.2 trillion total ($840B/year average) 2010 annual cost: $1.16 trillion (direct costs only) Recent estimate: $3 trillion/year (all costs included) Top 5 cancers: lung (15.4%), colon/rectum (10.9%), breast (7.7%), liver (6.5%), leukemia (6.3%) Note: China/US account for 45% of global burden; 75% of deaths in LMICs but only 50.0% of economic cost Additional sources: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaoncology/fullarticle/2801798 | https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-023-00634-9

.

120.

Care, D. Annual global economic burden of diabetes.

Diabetes Care: Global Economic Burden https://diabetesjournals.org/care/article/41/5/963/36522/Global-Economic-Burden-of-Diabetes-in-Adults 2015: $1.3 trillion (1.8% of global GDP) 2030 projections: $2.1T-2.5T depending on scenario IDF health expenditure: $760B (2019) → $845B (2045 projected) 2/3 direct medical costs ($857B), 1/3 indirect costs (lost productivity) Note: Costs growing rapidly; expected to exceed $2T by 2030 Additional sources: https://diabetesjournals.org/care/article/41/5/963/36522/Global-Economic-Burden-of-Diabetes-in-Adults | https://www.thelancet.com/journals/landia/article/PIIS2213-8587(17

.

121.

World Bank, B. of E. A. US GDP 2024 ($28.78 trillion).

World Bank https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=US (2024)

US GDP reached $28.78 trillion in 2024, representing approximately 26% of global GDP. Additional sources: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=US | https://www.bea.gov/news/2024/gross-domestic-product-fourth-quarter-and-year-2024-advance-estimate

.

122.

Cardiology, I. J. of. Annual global economic burden of heart disease.

Int’l Journal of Cardiology: Global Heart Failure Burden02238-9/abstract) https://www.internationaljournalofcardiology.com/article/S0167-5273(13 (2050)

Heart failure alone: $108 billion/year (2012 global analysis, 197 countries) US CVD: $555B (2016) → projected $1.8T by 2050 LMICs total CVD loss: $3.7T cumulative (2011-2015, 5-year period) CVD is costliest disease category in most developed nations Note: No single $2.1T global figure found; estimates vary widely by scope and year Additional sources: https://www.internationaljournalofcardiology.com/article/S0167-5273(13 | https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001258

.

123.

CSV, S. U. L. E. F. B. 1543-2019.

US life expectancy growth 1880-1960: 3.82 years per decade. (2019)

Pre-1962: 3.82 years/decade Post-1962: 1.54 years/decade Reduction: 60% decline in life expectancy growth rate Additional sources: https://ourworldindata.org/life-expectancy | https://www.mortality.org/ | https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/mortality_tables.htm

.

124.

CSV, S. U. L. E. F. B. 1543-2019.

Post-1962 slowdown in life expectancy gains. (2019)

Pre-1962 (1880-1960): 3.82 years/decade Post-1962 (1962-2019): 1.54 years/decade Reduction: 60% decline Temporal correlation: Slowdown occurred immediately after 1962 Kefauver-Harris Amendment See detailed calculation: [life-expectancy-increase-pre-1962](#life-expectancy-increase-pre-1962) Additional sources: https://ourworldindata.org/life-expectancy | https://www.mortality.org/ | https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/mortality_tables.htm

.

125.

Disease Control, C. for & Prevention.

US life expectancy 2023. (2024)